Where's the party at? Not on phone-fucked dancefloors.

“They’re watching themselves from the outside, rather than what dancers should be doing, which is being themselves from the inside.”

CONTEXT COLLAPSE AND THE STAR WARS KID

The plague of social media and the mobile phones it rides in on, like Bubonic fleas, has deeply fucked modern dancefloors.

I know this to be true, and anybody that's spent time dancing and/or DJ'ing in a wide variety of clubs, festivals, pub backrooms, underground raves, and private parties knows it to be true.

Increasingly, the best parties are those where phones are absent.

The cameras 99% of adults carry in their pockets every day, and the powerful surveillance software those cameras connect to, make it easy for anyone to rip any moment -- even our most intimate, silly, goofy, terrible, embarrassing, or happy moments -- and put it online for all to see, stripped of its original context. (Why people rip and monetize private moments is complex -- but it generally boils down to the design of the many systems that reward people for turning their lives and others' lives into content, especially the cottage industry of so-called influencers who make a living by attending and filming real-world events.)

The problem with all of this is that ripping private moments and putting them online causes context collapse. Context collapse is dangerous because it takes something that happened with one group of people and puts it out there for a global audience who don't have the same context.

In The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, Erving Goffman writes about the way we all segregate our audiences, saving one version of ourselves for one audience, and playing another version of ourselves for another audience. As an easy example we can all relate to, my kids should never know what I get up to in a bedroom. My bedroom performances are private, and leaked sex tapes are damaging to the people in those tapes (ahem: except when the tapes launch billion-dollar fortunes).

We're all familiar with the phenomenon of revenge porn — the nude that a malevolent boyfriend shares 'round the locker room and that escapes into the wild. We're familiar with the way people's wardrobe malfunctions, emotional breakdowns, trips and falls, and bad hair days get posted to and rack up millions of views on so-called social media.

The earliest victim of global, internet-enabled context collapse, Ghyslain Raza, became known as the Star Wars Kid when classmates discovered and leaked a private video he made of himself performing Star Wars-style lightsaber maneuvers. Raza became the first global video internet meme, racking up over a billion views before the first decade of the 2000s had come to a close.

The internet had its fun at Raza’s expense. Raza "had to endure ... harassment and derision from his high-school mates and the public at large" and required "psychiatric care for an indefinite amount of time." His family ultimately sued the families of the bullies who distributed the clip, and a settlement was reached.

Star Wars Kid: The Rise of the Digital Shadows | “I decided to have a little fun” | (Clip)

You see where I'm going with this, right?

CONTEXT COLLAPSE MEETS THE PANOPTICON

So context collapse is a threat we all live under. We are all Ghislain Raza, doing things in one room that might embarrass us (or worse) if shown to the people we hang out with in other rooms. There's a reason bedrooms have doors that close, and a reason why great parties tend to have a simple privacy rule that's easy to summarize:

what happens at <party> stays at <party>

This privacy commandment even covers the best meetings where attendees want to have more meaningful discussions. The Chatham House Rule, for example, is used by meeting organizers to encourage open and frank discussion around sensitive topics by forbidding revealing identifying information of meeting participants.

Why does it matter for dancefloors?

It matters because dancefloors and dance spaces where phones are present are now spaces where any dance moment could be ripped from this space and put online for views and for money, yes, but also for ridicule, for embarrassment, for ostracization, even for punishment.

For example, a closeted gay man might freely express himself in a place like Berghain, but lose his job at his conservative firm if his colleagues and bosses knew how he spent his weekend. The brave citizens who stood up to bigoted American policing in the events known as the Stonewall Riots fought for gay safety on dancefloors, and the context collapse that phones bring threatens that safety in a broader world where bigots still hold positions of power. Some countries still impose capital punishment for homosexuality, and domestic terrorists shoot up gay nightclubs. Safety is a real concern in these spaces.

And it’s not just gay folx that need protecting. A normie parent in the middle of a messy custody battle might lose the right to see their child if that photo of their powdered nose at the party were to be entered into evidence in the court battle.

Part-time sex workers who have been connected to their OnlyFans accounts have been fired from their jobs by Puritanically panic-stricken administrators; and some dancefloors are easily as wild as OnlyFans. People shouldn’t be fired for having a good time on the weekends, assuming they aren’t having performance problems during the work week as a result of their weekend revelry.

In short, I believe we all need places to express and perform and playfully explore our identities without fear of context collapse. But the now-ubiquitous phone camera that sits in every pocket makes this nearly impossible.

Would you believe that professional dancers are getting messed up by mobile phone cameras?

In this excellent NYT piece [free gift article from me for you] about the impact of phones and social media on professional dancers, Stacey Tookey, a dance instructor, discusses the importance of dance studios needing to be a place where students feel safe to fail, "but she now sees young dancers who are afraid of vulnerability or imperfection, anxious that a classmate might catch an unflattering moment on video."

Tookey told the Times, “They end up more concerned with what the clip will look like on social media than actually being present in the room,” Tookey said. “They’re watching themselves from the outside, rather than what dancers should be doing, which is being themselves from the inside.”

This phenomenon of monitoring your performance from the outside -- from the perspective of the global online audience that your dance performance might be seen by -- kills the dancer's connection to their emotions and stifles their creativity. It's like dancing on a stage. Most of us would dance quite a bit differently (or not at all) if we were forced to be in front of an audience to do it.

This is why the policy of banning photography and filming from dancefloors is such a critical element of the Magical Dancefloors scorecard:

In online debates that I really shouldn't be getting into (oh, the hours lost!), young people who have never known a camera-free dancefloor defend the use of phone cameras, making one or more of these arguments:

"I don't notice even notice the phone cameras, and neither should you"

"People only film the DJ on the stage, so you don't need to worry about the use of phone cameras"

"So what if someone's filming nearby, I ignore them and just dance"

"There aren't that many phones being used in this way, so no big deal"

"I only use my phone to grab a 30-second clip every song or so, and dance the rest of the time"

"OK, boomer, just accept that phones are here to stay."

"I hold my phone low so it doesn't block anyone's view, so it should be ok."

"I paid for a ticket, so I can do what I want when I'm on the dancefloor."

It's beyond the scope of this post to tackle all of those arguments, so I'll focus on just the statements that suggest that we should be able to ignore the cameras and have fun, that someone else's use of a camera shouldn't affect how we feel or conduct ourselves.

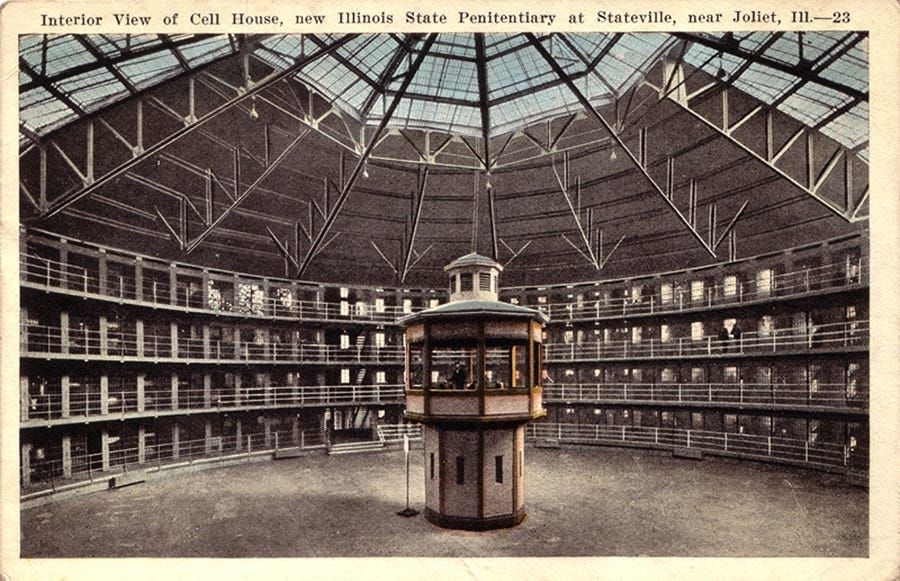

The folks making this argument are unaware of the concept of panopticism. Michel Foucoult explained the idea in his 1975 book Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison as a system of omnipresent surveillance that results in the inmates of prisons modifying their own behaviors to avoid punishment. Though it took a modern philosopher to lay it out so clearly, the system started in the late seventeenth century as a method for handling outbreaks of the Bubonic plague.

The anti-plague measures isolated people in their homes and used surveillance to ensure they stayed there: "Each individual is fixed in his place. And, if he moves, he does so at the risk of his life, contagion or punishment."

Honestly, that sounds like a lot of modern dancefloors where the plague of phones is present. To dance is to risk being ridiculed for being "cringe" or for caring. There’s a whole genre of Tiktok and YouTube videos where people who dare to dance expressively are ridiculed for doing so.

Foucault turns next to the discussion of the Bentham-style prison panopticon (pictured below) in which a central guard tower looks into prison cells, putting the fear of being observed (and punished for any infraction) into the heart of every prisoner, whether they're actually being watched or not.

Foucault's writing about the Bentham panopticon is fantastic and chilling in the way it predicts what has happened to modern dancefloors:

"The arrangement of [each prisoner's] room, opposite the central tower, imposes on him an axial visibility; but the divisions of the ring, those separated cells, imply a lateral invisibility. And this invisibility is a guarantee of order. If the inmates are convicts, there is no danger of a plot, an attempt at collective escape, the planning of new crimes for the future, bad reciprocal influences; if they are patients, there is no danger of contagion; if they are madmen there is no risk of their committing violence upon one another; if they are schoolchildren, there is no copying, no noise, no chatter, no waste of time; if they are workers, there are no disorders, no theft, no coalitions, none of those distractions that slow down the rate of work, make it less perfect or cause accidents. The crowd, a compact mass, a locus of multiple exchanges, individualities merging together, a collective effect, is abolished and replaced by a collection of separated individualities."

And, he might have gone on to write, if the inmates are people on a dancefloor, there's no danger of dance energy contagion. There's no copying of moves, no trading of smiles, no forming of groups, no interpersonal communication. Instead, everyone dutifully faces the DJ on a stage, and the crowd that had been collectively effervescing is turned into a collection of separate individuals, of content consumers facing and worshipping a stage.

Dancefloors had been places where it was OK to fly our freak flags, where dancing our hearts was the norm, where we didn't just communicate through the nonverbal language of dance, but also collaborated and built together something that rivaled whatever was going on in the DJ booth (the wellspring from which dancefloor energy emanated).

Any dancefloor that doesn't ban cameras is a dancefloor that puts dancers into a headlock that makes it uncomfortable to do anything other than obediently pogo-hop or side-sway while facing a stage. Power on these dancefloors is taken away from the dancers and given back to the organizers of the event and the owners of the brands on the stage. And the event itself, due to this policy, is no longer a dance party, but a "show" (to be watched). A mere concert.

The best of the many approaches to this problem is to simply sticker the cameras of phones and educate attendees on the importance of keeping the dancefloor safe from phones as is done at Berghain, Pikes Ibiza, SIX AM Los Angeles, and many other fine party establishments around the world.

Some establishments don't even need to sticker lenses because they're small enough to identify rule breakers and eject them. Stereo Montreal is my favorite example of such a space. And some of the underground events I've attended don't need to use stickers or sternly lecture partiers because their door policy is so careful about who gets in in the first place that the only folks who are allowed to enter are those that understand the importance of maintaining the sacred qualities of the dancefloor.

Great piece. Thank you. Always love to read some Foucault-based thoughts on modern culture (I wrote a piece on his work and yoga studios recently.)

I’m part of the generation who created rave. And everyone I know from those days perspective I have spoken to about this seems to agree that dance music and raves would never have happened if we’d had phones.

There will be less people who remember what it was to not have phones on the dance floor. It seems that there is a movement growing to reject phones in a small number of places but I feel the ones posting for the purpose of clicks and ridicule should face more consequences. What are your thoughts ?