A Love Letter to Berghain (Part 6/8): Berghain Itself

Happy Birthday, Jane Jacobs! You might've loved Berghain.

In this sixth installment of the "Love Letter to Berghain" series, I take a look at Berghain itself -- the institution, the building, and the way in which it all comes together to be greater than the sum of its parts. This one's a bit headier, and I've timed it to coincide with the birthday of Jane Jacobs (4 May 1916 – 25 April 2006), the influential thinker whose life work influenced urban studies, sociology, and economics.

The next installment in this series will be far more salacious and gritty -- consider this one a palate cleanser before the happy ending to the series. This writing comes from my belief that dancefloors are far deeper than we tend to give them credit for -- they're not only cultural institutions deserving of tax-advantaged status, but also essential spaces for making sense of life.

IīīīīI MEET ME AT THE EISBAR, EISBAR, EISBAR

A soundtrack for this section:

During Klubnacht, I made several visits to Berghain's famed Eisbar, the "shockingly good" ice cream parlor that sits in a room tucked above the main dancefloor. I had to visit this famed establishment because entire articles and appreciation threads have been penned in its honor.

My first attempt at entry happened during the Sound Metaphors party early Saturday morning. Eisbar was closed then, but a subsequent visit on Klubnacht, at about 3am Monday morning, met with success.

Eisbar sits above Berghain's flagship bar, off the main floor, up a narrow staircase. Upon entry, it felt immediately familiar, like a trendy coffee and ice cream shop one might encounter in a city center. Seductively lit with incandescent bulbs and accent candles that give the concrete and steel surfaces gorgeous texture, it feels like the sort of place you might take a date for an after-dinner affogato.

IīīīīI MAKKARONI SALAT

I peer into the ice cream case, but nothing there grabs me. Heresy, I know, but as a teen I worked in an American ice cream shop for six years, and have eaten my lifetime allotment of the stuff. I stroll over to the cold case at the far end of the small bar, past the barista pulling a double espresso shot for another patron. Earlier on Klubnacht, the case was stocked full of healthy delicacies such as chia pudding, bulgar wheat salad, and German-style potato salad. Now, at 4am Monday morning, all that remained was a few containers of "makkaroni salat" for about 7€.

I purchase one and sit with my back to the corner on one of the cosy black vinyl-clad couches, kick up my feet, and dig into the container with the flimsy eco-friendly bamboo fork. After seven hours of dancing and consuming nothing but secondhand smoke, my own sweat dripping through my mustache, a couple tabs of LSD, countless bottles of tap water, and electrolyte drops, the flavors of real human food overwhelm me.

That first bite of al-dente elbow macaroni swaddled in creamy mayonnaise cut with tart mustard makes my eyes roll back in my head. An involuntary moan escapes my lips. Too loud. I see movement out of the corner of my eye as the barman turns towards me with a look of concern. I give him the thumbs up and a stupid grin to show that I'm not having a seizure, I'm just loving what's in my mouth.

A feeling of ease and relaxation comes over me as I savor my macaroni salad while listening to the muffled beats Len Faki plays to the Berghain main floor. The food is almost too rich after so many hours without food, so I set it aside, and get to peeling the banana that I'd fetched out of my bag in the garderobe. This is a global banana and tastes exactly the same as the bananas back home. That's not a metaphor; sometimes a banana is just a banana, but to be honest, the white shaft of the peeled fruit does give me flashbacks to my darkroom visits.

I'm peeling an orange from my garderobe stash when a woman and her companion sit nearby. They've got ice cream, but I offer them half an orange to be friendly. They take it and the three of us sit there meditatively peeling orange segments and popping them into our mouths while their cups of ice cream sit melting. Nothing beats fresh fruit.

IīīīīI NATURE'S LIGHTSHOW

I get to talking with the woman, whom I'll call Noor here. She's from Jordan, now living in Berlin.

We get to talking about other dancefloors we've loved. She tells me about an event at the Sydney Opera house that impressed her with its magic, and I cry when describing the power of a full moon rising over a dancefloor of sand amongst the Joshua trees of a Southern California desert. She doesn't seem put off by my tears, so I just continue to talk right through them. I praise the way natural phenomena -- a full moon, a sunrise, a sunset -- seem to effortlessly open the emotional floodgates. These moments where our little spot on earth rotates into or out of the light of our life-giving star plucks the string of life that connects all of us to life, the universe, and everything.

This is why I believe the Panorama Bar shutters are Berghain's single biggest lighting achievement. When they're opened at just the right moment in the morning, after we've danced all night, the sun makes a mockery of all of the feeble, man-made lighting and shows us that the waxing and waning of sunlight that mark the passage of time is the bedrock experience of human existence.

IīīīīI JANE JACOBS ON BERGHAIN

In telling me about some of the dancefloors she's loved, Noor emphasizes that dancefloors have to be understood in their context -- be it desert or urban jungle. No discussion of urban context would be complete without Jane Jacobs, and we discover we're both huge fans of Jane Jacobs' work. We talk about the ways in which Jacobs' would have understood a place like Berghain.

Jacobs famously coined the concept of the "sidewalk ballet" in which the people of a city go about their lives in a way that at first seems chaotic, but that reveals an underlying, self-reinforcing structure. She wrote of the order of the city sidewalk, "composed of movement and change" that can be compared to dance.

She was careful to note that the dance of a vibrant sidewalk isn't like "a simple-minded precision dance with everyone kicking up at the same time, twirling in unison and bowing off en masse," but is instead like "an intricate ballet in which the individual dancers and ensembles all have distinctive parts which miraculously reinforce each other and compose an orderly whole."

It’s hard not to see Berghain in that sentence. The bustle and flux of bodies through its sidewalks, the choreography of collision and consent... to use Berghain's sidewalks is to continue the dance. Two strangers might slip by each other, one to the stalls for another hit of coke, the other to the dark room for another orgasm, their minds intent on their goals, their dancefloor-educated bodies effortlessly negotiating the bottlenecked passageways with a politeness and friendliness that wouldn't be out of place in a supermarket aisle.

Jacobs outlined four key conditions for vibrant urban life. Berghain, perhaps unsurprisingly, checks every box:

Mixed uses: Jacobs championed city blocks with a mix of spaces to live, work, eat, gather, and play. Berghain is a mixed-use marvel. Beyond its dancefloors, it contains bars, dressing rooms, lounges, darkrooms, art galleries, and of course, the Eisbar. Legal and illicit economies intersect on its street corners and in its dark corners. People consume nourishment and each other, in acts both sacred and profane.

Small blocks: Jacobs advocated for smaller city blocks with frequent street intersections to support walkability, social exchange, and "natural surveillance" between pedestrians and other sidewalk inhabitants, from shop-keepers to children at play. Small blocks result in more interconnection, and ultimately, more trust: "The trust of a city street is formed over time from many, many little public sidewalk contacts... Most of it is ostensibly trivial but the sum is not trivial at all.”

Berghain's rabbit warren of intersections, corners, cubbies, hallways, bathrooms, bars is designed to have few dead ends to keep traffic flowing and to make it easy for people to cruise each other. Criss-crossing Berghain's spaces over the course of my weekend, I ran into people I'd encountered hours earlier on a dancefloor or in a bathroom line, each reunion making me feel a touch safer and more at home. I could see how, over the course of several weekends in this place, I would feel at home here.

Density: Jacobs believed that just-right density leads to more vibrant on-street interactions, with a key benefit being the safety that comes from many eyes watching the street at all times. She wrote, "Large numbers of people entertain themselves, off and on, by watching street activity.”

From a density perspective, Berghain's door team performs the essential role of zone enforcers and city planners by keeping density levels on its sidewalks just right by carefully filtering and dripping partiers in until the space is filled with lively interactions, but not so full that rooms feel cramped. They build density slowly, allowing it to peak then slowly dwindle through the weekend, cutting off re-entry when the final DJ begins their set to heighten the intimacy of the final eight-hour stretch -- this is when Berghain's energy is purest.

When densities are just right, Jacobs notes, "incidental play" emerges. People spend their time on sidewalks "loitering with others, sizing people up, flirting, talking, pushing, shoving and [engaging in] horseplay." I detail some examples of "incidental play" that happened on the Panorama Bar dancefloor in part 3 of the series, here.

Mix of economic activities: Jacobs believed that vibrant cities have strong local economies where goods are produced and consumed within close proximity. Though I never witnessed money changing hands, the signs of vibrant local commerce were evident in the dilated pupils all around me.

Noor and I didn't have a copy of Jacobs' book open in Eisbar. But as we talked, I found my understanding of Berghain expanding to include not just everything happening within its walls, but also the cultural context in which Berghain came to exist.

Noor and I didn’t lay this out so systematically. We didn’t have Jacobs' Death and Life open on the bar. But our chat helped me understand that this fortress of concrete might feel like chaotic hedonism, but was actually structurally rigorous, while being soft enough to allow for real life to blossom there, emergent and elastic. A micro-city. A dancefloor democracy.

IīīīīI THE DEATH AND LIFE OF A GREAT BERLIN DANCEFLOOR

To understand Berghain, one must understand what came before Berghain.

In 1988, Berlin's first permanent venue, UFO, opened in what used to be the potato cellar of an apartment building. A literal hole in the ground. It had no ventilation system and was lit by candles.

When the wall that divided Berlin fell a year later, in November 1989, and the East German administrative state fell apart, it happened to occur just after Europe's awakening to the power of raving via the "Second Summer of Love" (1988 - 1989). Additionally, the genre of techno, first developed in Detroit, had blossomed and had begun to take hold on dancefloors around the world.

Raving. Techno. Reunification. Unrelated, but simultaneous -- a perfect accident. The Wall fell in a socio-political rupture that both reunified and broke the city, and techno grew in the cracks like weeds in a city sidewalk. In Der Klang Der Familie: Berlin, Techno and the Fall of the Wall, Felix Denk and Sven Von Thülen describe the happy coincidence that birthed the Berlin techno scene that we still enjoy today:

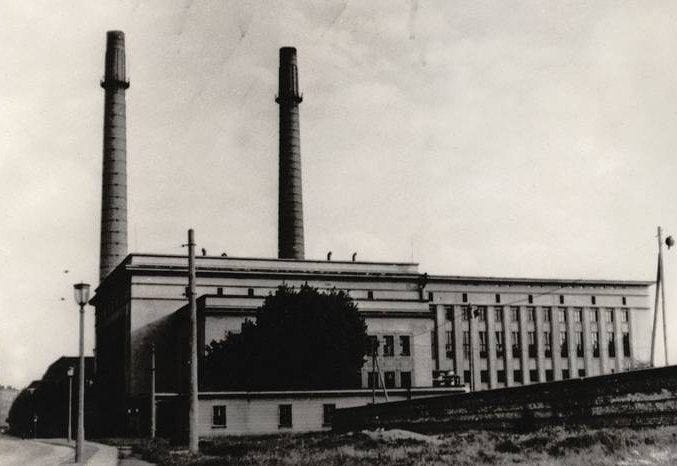

"This new, raw, stark machine music appeared -- and then the Wall came down.... With no authorities involved, cells of ravers from across the city built a new scene together on the temporary dancefloors of forgotten banks, supermarkets and power stations -- the type of spaces that anarchist Hakim Bey described as 'temporary autonomous zones'.... Suddenly, there were all these spaces to discover: a panzer chamber ... a World War II bunker, a decommissioned soap factory... a transformer station .... and suddenly, people were dancing at all these sites rejected by recent history, to a music virtually reinvented from week to week."

Berlin's first club dedicated to techno, Tresor, opened March 1991 in the abandoned, subterranean vault of the former East Berlin department store Wertheim.

Before the 90s were out, many clubs had opened and closed, with Ostgut, Berghain's predecessor club, opening in 1998 to play techno for gay men. When Ostgut lost its lease in 2003 due to pressures of redevelopment, it was relocated to and reincarnated in the building it now inhabits, and given the name Berghain.

IīīīīI BERGHAIN'S SAVVY

This quick and shallow history lesson places Berghain in the context of global music (techno, raves), geopolitics, and gay culture, but it doesn't explain Berghain's ability to survive, thrive, and rise to the zenith of global club culture.

A lot of the club's success must be credited to the smart moves made by Berghain's leadership to position the club as a cultural institution (and not a mere entertainment venue) in a legal battle that began in 2008.

Freakonmics covered this battle, "Government tax agents walk into Berghain, presumably without needing permission from Sven. They’re there documenting everything they see. Asking a question: From a tax perspective: what is happening in these rooms?"

The officials were trying to reclassify Berghain as mere entertainment (e.g., casinos, porn theaters) so that its income could be taxed at 19 percent, rather than the 7% rate that "high culture" institutions such as opera houses and museums enjoy.

Berghain ultimately triumphed in court, arguing successfully that what happened in Berghain was high culture. A key argument supporting their legal case was the fact that attendees came to enjoy the work of specific artists (this is one reason why the security frequently ask those who would gain entry which acts they've come to see -- this question provides ongoing reinforcement of the "high culture" argument).

The tax break, and the smart purchase of the building in 2011 from the energy company they'd been paying rent to, gave Berghain the sort of financial security that would be essential to its ability to survive not only the 2020-2022 global pandemic, but also the clubsterben (English: "club death") malaise that had, by 2024, struck down many fine Berlin clubs.

But I'd argue that the majority of Berghain's success can be credited to the genius design of the entire experience -- the Jane Jacobs-like intentionality of architecture decisions that culminate in a vibrant cityscape of diverse needs, activities, and behaviors that take place at the intersections, on the sidewalks between its dancefloors, and in the cubbies and darkrooms through which 2,000 to 5,000 strangers flow every weekend.

Jane Jacobs described a vibrant city sidewalk as a place where "An immense amount of both loitering and play goes on in shallow sidewalk niches out of the line of moving pedestrian feet.” She could just as easily have been talking about the cubbies at the backside of the Panorama Bar space, the lounge above Pano's bathrooms, the tucked-away bars, and the Eisbar.

Vibrant cities contain enough flexibility for the real patterns of life to take place. Suburbs, in their attempt to clean up the disorder, trash, and ugliness of cities, regulate humanity to the sidelines. “There is a quality even meaner than outright ugliness or disorder, and this meaner quality is the dishonest mask of pretended order, achieved by ignoring or suppressing the real order that is struggling to exist and to be served.”

Making a space where the real order could be served is where Berghain's architects (not necessarily the firm that designed the space, studio karhard, but the team that directed the architects' work) showed restraint. Like enlightened city planners, they laid out the space, they set up a few key regulations, and then stepped aside to let the inmates run the asylum. Emergent behaviors and vibrant expression followed, messily and beautifully exploding all over everyone within the confines of this one city block of a building.

What exactly is the "real order" of Berghain? In part, it's a function of the people who show up every weekend. Not just the regulars, but the new blood who create essential frisson by introducing new ways of being, thinking, and behaving. As with most cities, Berghain has long struggled with the tension between residents and immigrants.

Tobias Rapp's description of the club beautifully captures this dynamic:

"On a dance floor full of hardened Berlin techno veterans, everyone knows what the score is, but sometimes they can lack the necessary enthusiasm when the DJ slams the bass back in after an eight-beat pause. It's just that they've heard this track a few times already. If you replaced this whole crowd with young, gay Italians who were at Berghain for the first time and really getting their rave on, it probably wouldn't matter what track was playing -- they'd go crazy every time. But the combination is wonderful. Nothing can beat a dancefloor which has been formed over the years, which knows what to expect from what DJ, and is nevertheless capable of breaking out of these patterns from time to time."

Agreeing with Rapp's analysis, Luis-Manuel Garcia, an ethnomusicologist who studies techno at Berlin’s Max Planck Institute for Human Development compared clubs to island ecosystems: “For a scene to be lively and coherent, it requires turnover but also a certain amount of stability... If a scene becomes too insular, it tends to stagnate, but if it is suddenly overwhelmed by newcomers, the elements that created it begin to dissolve."

The door also controls the critical mix of new and old partiers, keeping the veterans invigorated and challenged with just enough -- but not too many -- newcomers while simultaneously keeping them in check with a foundation of mentors who know the rules.

This is a problem the city of Berlin struggles with overall. Tourist dollars contributed about €10B to Berlin's economy in 2019, but not without the side effect of driving the cost of living higher for Berliners, creating tensions that bubble up into protest, including the evocative graffiti pictured below, which can be translated to "fist tourists." Perhaps the graffiti artists know the locals do exactly this to tourists at Berghain's Lab.oratory, where Crisco is helpfully sold at the bar, perhaps not:

Berghain's door, once again, holds the key to managing this tension.

IīīīīI THE REAL ORDER

But that still doesn't answer the question posed above. What's this "real order" of Berghain? Why do we go? What are we getting out of it? What animates every human partying there or supporting the party? What is the "high culture" of Berghain?

My answer to the "real order" question is: art. People flock to dance music because it's an artform that requires bodily participation, and that embodiment helps us make sense of life and our place in it. To dance is to art.

Ernest Becker, cultural anthropologist, writing about our attempt to make meaning out of life, wrote about the "new [at the time] cult of sensuality that seems to be repeating the sexual naturalism of the ancient Roman world."

Becker says this cult is one that lives "for the day alone, with a defiance of tomorrow; an immersion in the body and its immediate experiences and sensations, in the intensity of touch, swelling flesh, taste and smell. Its aim is to deny one’s lack of control over events, his powerlessness, his vagueness as a person in a mechanical world spinning into decay and death."

So far, Becker seems to have our number as surely as if he'd been right there in Klubnacht with us. Lest we feel judged, however, he continues: "I am not saying that this is bad, this rediscovery and reassertion of one’s basic vitality as an animal. The modern world, after all, has wanted to deny the person even his own body, even his emanation from his animal center; it has wanted to make him completely a depersonalized abstraction. But man kept his apelike body and found he could use it as a base for fleshy and hairy self-assertion—and damn the bureaucrats."

Again, the door is the essential piece that makes Berghain's cult of sensuality possible: it creates safety for reassertion of our basic animal vitality not only through swelling flesh, tastes, and smells, but also through overwhelming auditory sensations that drive from our heads all of modernity's kruft. Berghain is where we both throw off the chains of our subservience to the bureaucratic horrors of capitalism and reacquaint ourselves with the truth of animal bodies that were meant to dance, sweat, and fuck, not fold into ergonomic chairs designed to lengthen the duration with which we can squint at rows in a spreadsheet.

IīīīīI JUST A STALE DISNEYLAND FOR ADULTS?

Michelle Lhooq (of the Rave New World Substack) criticized the club after a "rather bleak time partying at Berghain." She faults Berghain for its "putrid, animal trough-like bathrooms" and "the fact that the club doesn’t even offer free water!!!" and, ultimately, for a pervasive "self-consciousness performativity" thanks to the "flattening weight of the internet."

I saw glimpses of people "performing Berghain" at Berghain, especially the newcomers who hadn't yet been through the cleansing crucible of an epic Klubnacht weekend. But by 6am on Monday morning, after Klubnacht had matured over the course of 30 hours into a full and sweet ripeness, after the door had been closed for six hours to re-entry, people were too exhausted to perform their identities with the same gusto, instead showing up with a raw vulnerability that both stank of birth and glistened like a wound.

I don't understand Lhooq's complaint about the lack of free water. I easily found a glass bottle, cleaned it off, and quickly filled it with ice cold potable water some 20 or more times over the course of my weekend there. I think people sometimes forget that tap water is potable. I found Berghain's infrastructure admirably up to the task of keeping thousands of people alive and healthy. Whereas Lhooq found Berghain a "soulless simulation of cool" and a "techno Disneyland,” I found it to be a place of relaxed lawlessness reincarnated from the ashes of a temporary autonomous zone (Ostgut) that was itself built on the ruins of a temporary autonomous zone (post-wall GDR).

Still, perhaps there's something to this Disneyland angle, so let's hear it in different words from another writer, this time Shawn Reynaldo (who writes the First Floor Substack), who essentially agrees with Lhooq when he wrote, in his book First Floor Volume 1, "People, fueled by the legend of places like Berghain, have clear expectations of what a night at the club is supposed to be like, and will eagerly dress up to play their part. (It’s not a coincidence that so many of today’s party people are still dressing up like characters from a fetish porn spoof of The Matrix."

Fashion photoshoots, such as this one from Paper Magazine, only perpetuate the superficial myths of what it means to look like you belong at Berghain:

As evidence of Berghain's staleness, Reynaldo cites the "clichéd images that DJs tend to post on social media," specifically "the obligatory post-gig photo in front of Berghain" in which the DJ who just played a set "posts up in front of the hulking former power plant and takes a photo, which is then usually shared with a gushing caption that may or may not resemble the quasi-motivational tone of a high school valedictorian's graduation speech."

Reynaldo continues: "In some ways, the sound of techno has become almost secondary. It’s the vibe and aesthetic most audiences are after, and while promises of unbridled hedonism and wild, round-the-clock partying do tend to have a wide-ranging, evergreen appeal—which has undoubtedly helped fuel the genre’s commercialization and the influx of “normies” into nightlife—it’s nonetheless telling that even as the music has changed, so many other aspects of the culture have not."

Again, I think the analysis relies too much on an outside-in analysis of Berghain that's not been tempered by a dive into Berghain's real and alive vibrancy. Perhaps Lhooq and Reynaldo made such dives, but there's no evidence that I can find in the writing they've published. It just doesn't feel fair to hate on a thing because it's been meme-ified. Memefication comes for everything that achieves a certain level of global awareness.

Patrick Hinton defended Berghain against meme-ification charges, writing, "Its meme status is of no detriment to its reputation, it just so happens that in 2016 cultural significance unfolds online in disposable-yet-celebratory internet humour." It's just the internet doing what the internet does.

That said, it's certainly a good deal less underground than it once was, which leads some cool hunters to look elsewhere. But I think Berghain's still rich with secrets and opportunities for discovery, even for jaded internet natives who think they know the place, having consumed memes about it for more than a decade.

In the end, the question we should be asking isn't whether Berghain still matters or has become Disneyfied. Rather, we should ask "why does Berghain continue to matter, when other cultural institutions have faded or succumbed to death?"

Because it was never just a club.

IīīīīI MEMORY PALIMPSEST

To praise Berghain's features in isolation (e.g., darkrooms, lounges, balconies, lighting fixtures, high ceilings, cold water taps) feels myopic. We can't just tally up all of the support spaces that make it easy for people who need a break from dancing to do drugs (or a break from drugs to do dancing). We also need to understand how the space supports people who need to fuck, to cuddle, to splash cold water on their faces, to get refreshments, to sit with their head down at the bar, swirling their drink while trying to read in the melting ice cubes an answer to what they're doing with their lives.

The thoughtful details reveal the soul of the place, and the soul of the place is imprinted on partiers through the layers of memory that's scratched into the wax of our brains as we bounce from room to room, absorbing memory and incorporating it through repetitive movement on and off Berghain's dancefloors.

I remember the ecclesiastical bloom of color in the smoke-hazed air as morning sun streamed through the east-facing stained glass between Panorama Bar's drug dens and the bar-adjacent smoking area. Mein gott, spicy sacrilege!

I remember a couple crouched in a cubby off the Panorama dancefloor, one head held in place by interlaced fingers in an act so tender and explicit it seemed beyond transgression. Nearby, separated only by a thin wall of plywood and no door, another pair lay tangled in each other, smoking post-coital cigarettes, their affections natural and unremarkable inside the umbrella of shared trust.

I remember the toilets. The Pano bathrooms felt like zoo stalls for human mammals in various states of undress, grooming, and veterinary supplementation. Elsewhere, floor-to-ceiling stalls offered true privacy. These spaces affirmed and supported our mundane and sacred, erotic and excretory ape rituals.

I remember the water taps: industrial, indestructible, and ice-cold. The kinds of taps found on the sides of houses, built to kick open when your hands are caked with gardening soil. In Ibiza, I’d paid €18 for .33L of plastic-tasting water. At Berghain, hydration was non-negotiable and infrastructural, not another opportunity to make people regret not buying into a VIP table.

I remember the club’s peculiar ability to both decay and renew itself. On Saturday morning, the sink basins were clogged with hair, cigarette butts, and half-dissolved beer bottle labels. By Saturday night, they gleamed again. This den of iniquity could be wiped clean and dressed for church by a cleaning crew who mucked out and hosed away the past in a matter of hours.

I remember the Asian boy who emerged from nowhere, interrupting my conversation with Noor. A 20-something twink: tiny, lithe, and unmistakably in his element. He climbed a couch, stepped onto a tiny lip of concrete, and reached up for his phone that had been stashed in a hidden charging nook ten feet off the ground. He grinned at our astonishment. “I know all the secret spots,” he said, beaming with the pride of a church mouse who steals Eucharist nibbles. "I basically live here," he said, then disappeared into the shadows.

I remember the dog tags at the coat check. Mildly militaristic metal-and-nylon necklaces built for rough play. I remember the taste of salt on the cord right after it had been handed to me, evidence that this place had existed before now, and wasn't just a dream, and a comforting breadcrumb trail back to civilization, should I find myself lost.

I remember watching people cache their drinks in improbable places: ledges 8 feet high, pockets behind columns, atop steel dividers. The tall had secret privileges. The clever, even more.

I remember the candle holders in the Eisbar, as big as volleyballs through years of accumulated ash, wax, and history. Silent witnesses to confessions, propositions, breakdowns, and bliss. Perhaps my macaroni salad moan had been recorded in wax. I wanted to ask the bartender when they’d last been cleaned. I suspected the answer was never.

I remember the absence of mirrors and how I enjoyed reading my face by looking at others. I attend my college and grad school reunions every five years because they're a powerful memento mori, showing me the passage of time, something that's hard to detect in the mirror every morning. When I see a face for the first time in five years, I see in their face proof of my own big leap towards death. Similarly, at Berghain, I didn't need to see my face reflected back at me, because I could observe my ferality on the faces of my peers. At some point, we all looked like grimy kids who had been playing tag until called in for dinner: faces flushed, hair sweatily pushed out of our eyes, collars stretched, buttons unbuttoned, zippers half closed. But what I saw more than anything else in their faces was joy: like children, we glowed.

I remember the sticker-covered stairwell connecting the FLINTA toilets to the ground-floor exit. I cooled off in this stairwell a few times and enjoyed browsing the layers of pornographic stickers and graffiti tags. I hadn’t brought stickers or a marker on my first night, a mistake I corrected by sneaking in a fat marker on my next visit. Encountering this stairwell felt profound because it sat outside the reset bubble. The graffiti and stickers were allowed to accumulate. We were allowed to leave behind some small part of ourselves, some proof that we had been here, that we had existed, and this felt anchoring.

Berghain isn't a list of parts, it's an intentionally designed experience that trusts its citizens to wander, discover, and play. Berghain doesn’t present itself all at once, it must be earned, layer by layer.

I appreciate the rigor with which you write about Berghain. Entertaining and thought provoking.