Dancefloor Thunderstorm: A Love Letter to SoCal Rave’s Peak Years

First in a series of book reviews

First in a series! This is my first book review for MagicalDancefloors.com, and I’m starting with Michael Tullberg’s Dancefloor Thunderstorm, a document of Southern California rave culture at its late-’90s peak. If you’ve ever wondered what we lost (and what we kept), this one’s a time machine. And if you’ve got other dancefloor-related books I should read and review, drop them in the comments.

⛈️ Studying dancefloors with a lens

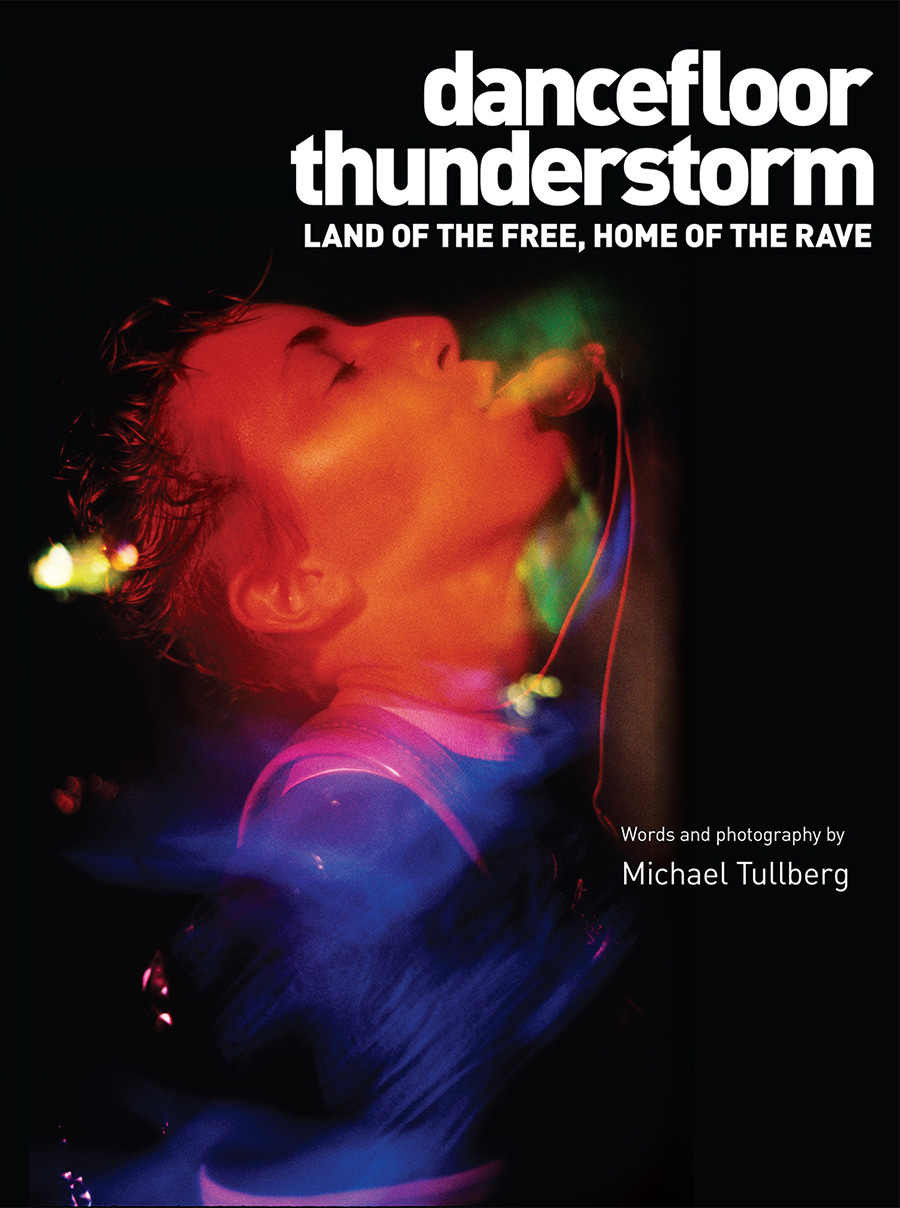

Michael Tullberg is a prolific North American music photojournalist whose work has appeared in publications including Rolling Stone, SPIN, and Mixmag. His photographs from the front lines of the Southern California rave movement during its peak era of 1996–2002 are mixed together here with interviews, essays, and supporting photography in a beautifully-bound, 308-page book titled Dancefloor Thunderstorm: Land of the Free, Home of the Rave. I can’t imagine that there’s a better book in existence covering this period and this region. If you know of one, please point me to it.

You’ve probably heard the old adage that “writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” Where does that leave photojournalism of raves? Is it as useful as whistling about quantum physics?

I don’t buy the idea that music can’t be written about or studied. It’s obvious to me that a deep understanding of any subject requires that we sometimes pin it to a corkboard with a needle so that we can study it under stillness and with magnification. Whether the student (or critic or journalist) of music uses a pen, paintbrush, or lens, I believe they’re capable of revealing deeper truths than we might arrive at by simply listening to high-fidelity recordings of that same music. Photography and photojournalism likewise reveal truths about music that are otherwise inaudible, so I’m personally a fan of books like Tullberg’s, even if I simultaneously believe that ubiquitous phone cameras are a pox upon today’s dancefloors.

Tullberg says he wanted to show the scene from the perspective of someone who was actually there—and to capture the “little things…the almost unnoticed nuance” that cements memory. The book delivers on that promise.

I’m also thankful that it wasn’t full of portraits of DJs in heroic and egoic power poses—that’s in part due to Tullberg’s focus on the dancefloor and in part because the images in this book largely predate the era of the superstar DJ. There is a section of DJ portraits, but that section doesn’t feel as adulatory as modern-day DJ portraiture.

I came for a history lesson—and to see what the late-’90s would reveal about the rave present. Would the photographs reveal how much has changed, or would they reveal how much has stayed the same?

The answer is paradoxical: more continuity than I expected, but more difference than I wanted.

⛈️ Photos that show what it was like

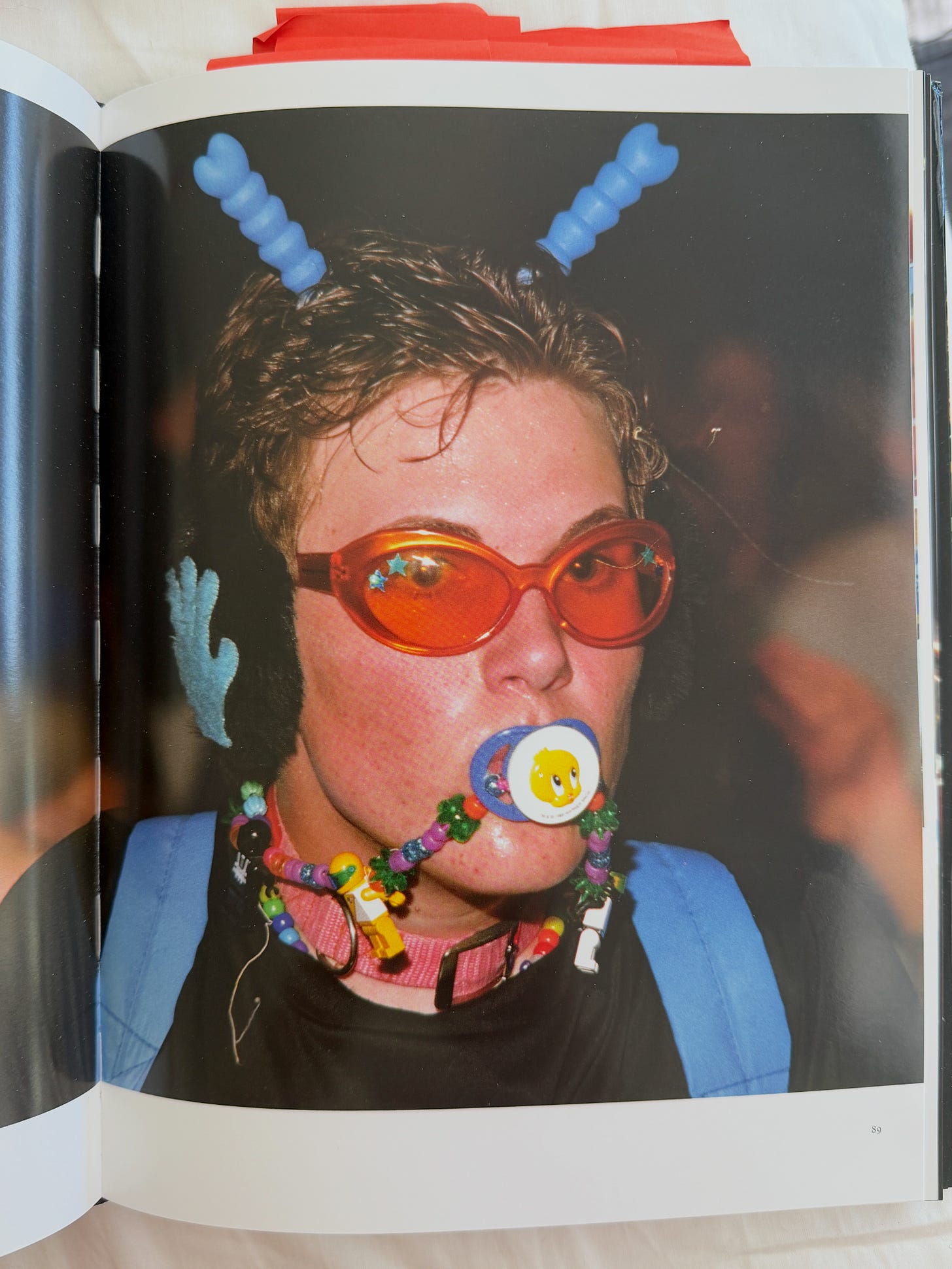

The ravers of 30 years ago looked a lot like the ravers of today. They wore fun outfits, they sweated buckets while dancing, they took drugs (perhaps better ones than you’ll commonly find on today’s dancefloors, but certainly often without today’s harm-reduction norms). In some ways, though, these people from Southern California’s first rave generation look alien. For example, a number of Tullberg’s subjects have baby pacifiers in their mouths or hanging from necklaces. These once-popular oral fidget toys helped ecstasy ravers avoid the common side effect of chewing their lips into bleeding pulps, but they’ve gone out of style and are rarely seen today.

Likewise, the super baggy shirts and pants of the 90s -- often plastered with ironic brands such as mascots from sugary children’s cereals -- offer a marked contrast to today’s much more revealing, skin-tight outfits with understated logos, if any. The baggy clothing many of Tullberg’s subjects wear doesn’t look like the best stuff to sweat in, so we’ll give modern ravers a point for superior heat and moisture wicking, even if the prevalence of highly conformist outfits worn by the hordes of Temu Berghain, Pashbro, and Alo Yoga raver normies has resulted in less diversity of dress overall.

Another insight gleaned from poring over Tullberg’s photos: I learned that modern ravers tend to take better care of their ears. Few of Tullberg’s subjects can be seen wearing ear protection, likely resulting in permanent hearing damage that many of them would come to regret. Hearing protection hadn’t been normalized yet. Score another point for the health consciousness of modern ravers.

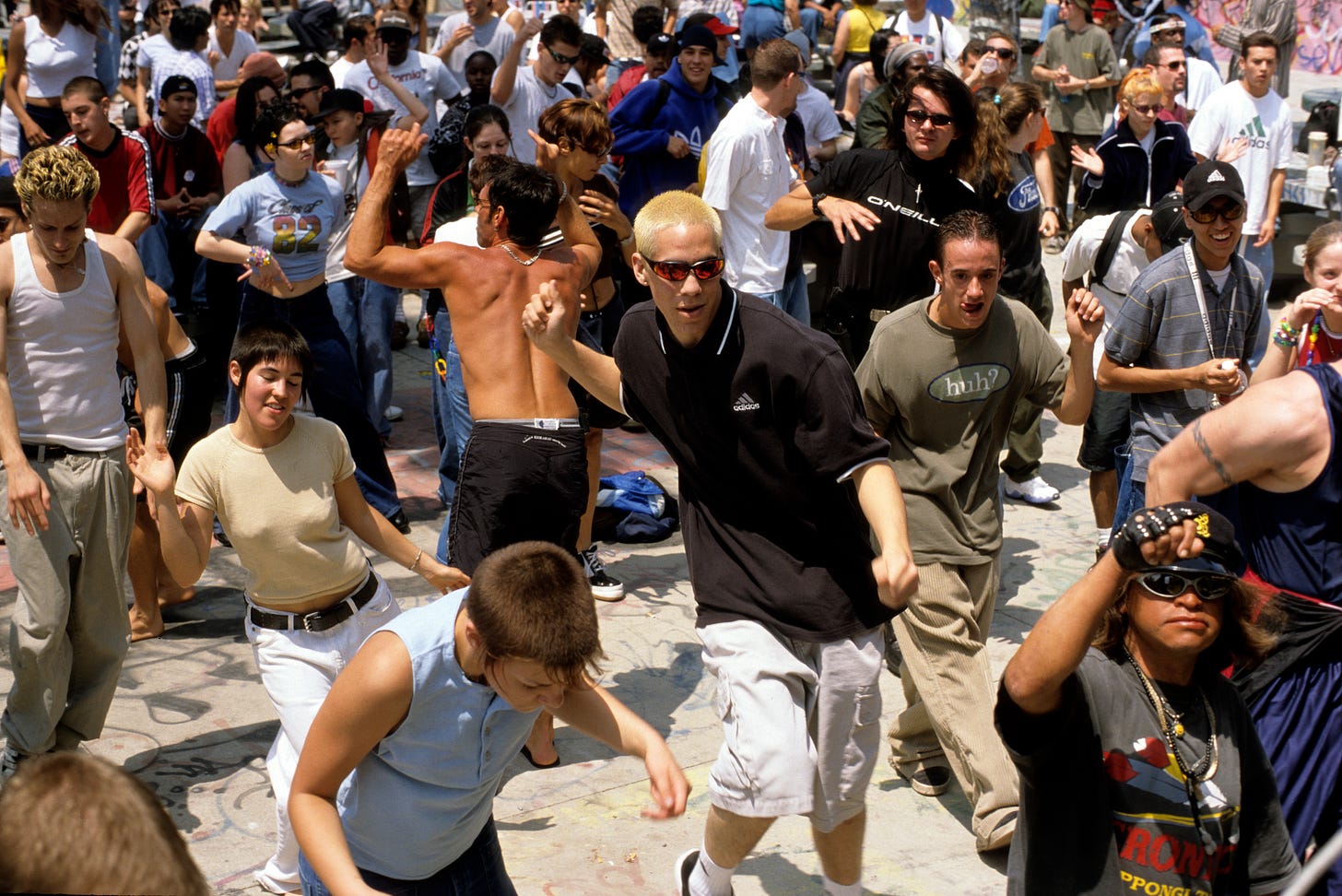

On the other hand, there’s far more evidence of dancing in these photos than one will find at many of today’s so-called raves. All of the photos in this book pre-date the smartphone era—starting around 2007—when being recorded made everyone more self-conscious, even afraid to dance. Tullberg’s lens wasn’t connected to social media in the same way that phone cameras are today, and doesn’t generate the same fear of being ridiculed online nor the same desire to perform for the vast context-collapsed, internet-connected audience as a smartphone does.

As a result, Tullberg’s lens reliably finds scenes of vulnerability. A blissed-out couple hold each other, eyes closed. He seems to be nibbling on her neck, she holds his hand and clearly seems to enjoy being nibbled upon. In another scene, a woman in a halter top dances, both arms in the air. The smile she wears isn’t performed for anyone else. She’s just feeling the music. On another page, at another rave, a woman in an Adidas tennis visor and an oversized Nike soccer jersey is caught mid-move, one palm down, the other palm up, and it’s easy to fill in the blanks to picture the rest of her dance move, because the shot has caught her at the exact right moment to make it easy for our minds to fill in the blanks thanks to the strength of the personality that shines through the page. Another photo features a cuddle puddle of Asian ravers decked out in kandi and tattoos, tangled happily and platonically in each other’s limbs.

The through-line in many of these images is unselfconsciousness.

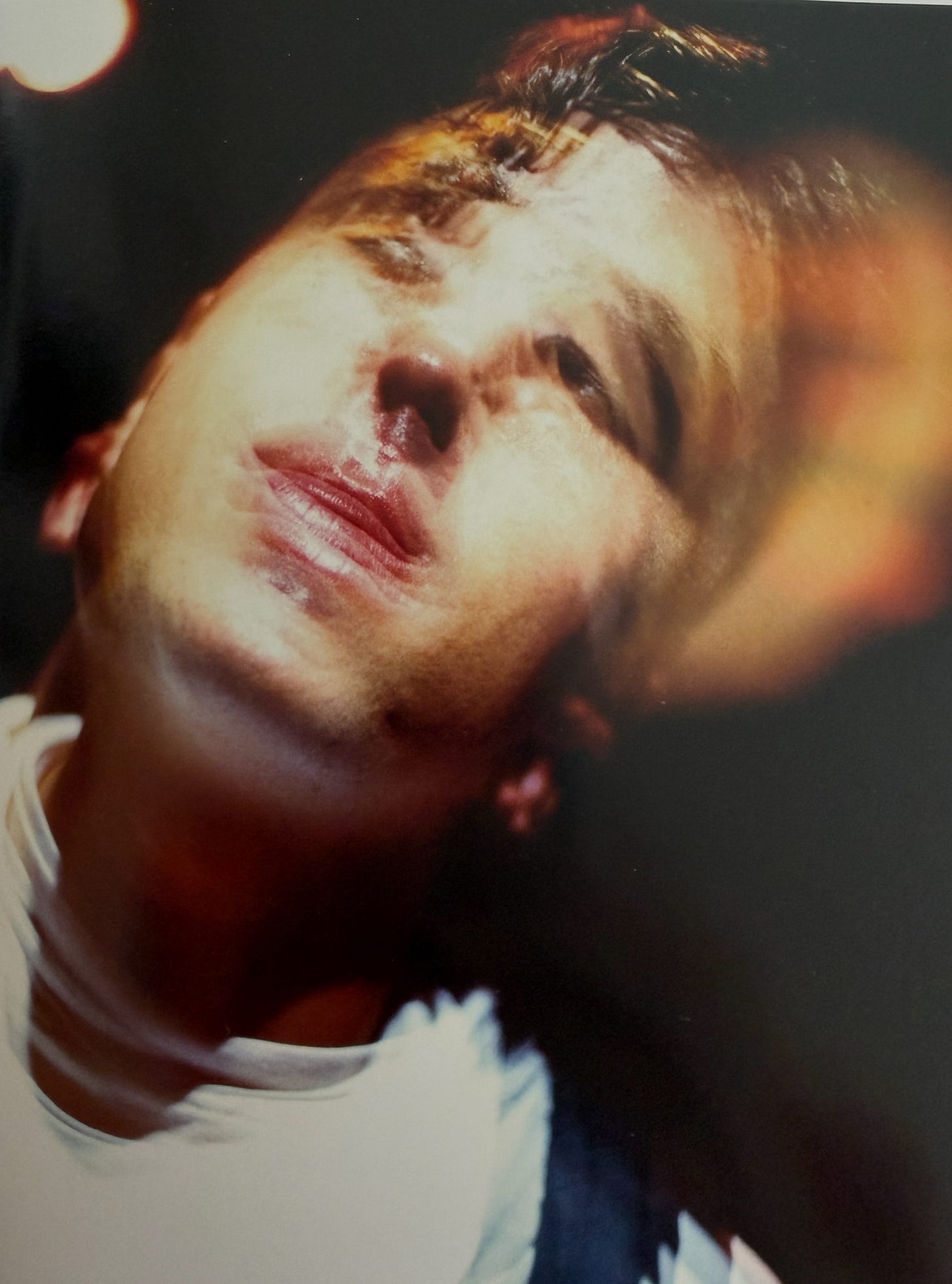

In one of my favorite images (included above), Tullberg employs long exposure to capture the sort of ecstatic hands-in-the-air dancing familiar to pretty much everyone who’s ever gotten lost in the rave sauce. The central figure is having a moment, the strobe capturing his movement through time. The strobe flashes reveal an interesting game of peek-a-boo. In one moment, two faces look directly at the lens, in the next strobe flash, they’re looking away, reminding me of the ways in which dancers often steal looks at each other. These surreptitious glances are part of the social experience, and it wasn’t until I saw them in this image that I remembered the countless micro-moments of watching and being watched by the friendly folks all around me.

For me, Tullberg’s strongest images are those in which he tosses the photographic rules of exposure and clarity in favor of images that, like the image above, capture the ways in which light, movement, and mind-altering substances play tricks on our senses. These distortions of reality feel more true and more representative of what it feels like to be a participant in a rave than a straight or undistorted photo of the same scene could ever convey. The silhouettes above -- from a Sugar Beats party in 1996 -- were captured in what Tullberg tells us were sauna-like conditions in which condensate of sweat dripped from the ceiling.

Tullberg’s artful distortions sometimes convey intense solitude. At other times they suggest intense companionship. At times, his subjects look like blissed-out angels drunk on love. At other times, they look like burn victims, such as in this image that reminded me of all of the times I’ve seen faces morph monstrously under the influence of hallucinogenic lighting.

Such a trove of images could’ve only been captured through the trial and error of thousands of shutter presses and a deep understanding of the essence of a scene built by spending lifetimes lost in the intoxicating sauce of the California rave scene during its 1990s peak. As a photographer trying to figure out how to capture the essence of the scene -- the ways in which it made its participants feel aren’t readily captured by the physics of light entering a lens -- Tullberg developed a photographic style that turned challenges such as low light, flashing lights, and movement to his advantage.

⛈️ Stories, too

One standout chapter recounts what Tullberg calls the “mother of all LA rave busts,” a rave and a raid that demonstrated the era’s moral panic.

The “Seventh Heaven” rave of December 31, 1996, was busted by 150 LAPD officers who faced off against ravers chanting ‘Rave Till Dawn! Rave Till Dawn!’

Tullberg tells us that the LAPD used tear gas, rubber bullets, and concussion grenades to bust a rave that came to their attention after dozens of partiers were made sick by an industrial solvent-laced concoction being marketed as “Herbal fX” by an unscrupulous dealer.

His extended account here in Insomniac magazine is much more colorful than the version included in the book, and the event became news reported by the national media, part of a trend of alarmist coverage that ultimately culminated in then Senator Joe Biden championing the 2003 RAVE Act (Illicit Drug Anti-Proliferation Act).

Footage of the raid was taken with a handheld video camera by someone who had been stuck in the adjacent parking structure.

Another story involves Prince bringing his test pressing of the Batman soundtrack to a club, where he asked Mark Lewis to play two tracks off of it so that he could hear it in a club-level soundsystem.

⛈️ The dancefloor was the heart of this era's raves

Some of the most important changes to raving over the last 30 years come out through the book’s ample texts. Some of Tullberg’s writing is featured, but I think the interviews with DJs of this period are particularly interesting. In his interview with Christopher Lawrence (”one of the original purveyors of the West Coast progressive trance sound in the 1990s”), Lawrence compares the ‘90s rave scene to punk:

Lawrence: “You can draw a lot of relations with punk. The punk bands were just guys doing it themselves, same as the DJs. You didn’t have booking agents back then. The promoters just contacted the DJs directly.... Everybody was just doing it for ... I dunno! It was about the parties, it was about participation. Up until then, you were always part of the audience, whereas at these early raves, if you remember, there was no DJ booth.”

Tullberg: “No, it was on the floor.”

Lawrence: “It was just a card table that they put the turntables and mixer on. And generally the DJ was never the focal point. There were no lights spotlighting the DJ. The lights surrounded the room and focused on, like, visuals on the walls and lights on the dance floor. There was no focus on the DJ. The DJ was usually in the dark and there’d be a group of kids hanging around.”

Tullberg: I have pictures of exactly that. You at the Alexandria (Hotel), with kids just surrounding you like that.

Lawrence: “They wanted to see how the DJ was mixing, or whatever. But generally, the focus was the party, and not the DJs. It was about being an active participant in the event. The kids would dress up and pick out their outfits. You’d be on the dance floor with your friends. ... The audience was a participant, they weren’t just spectators.”

I think this exchange captures one of the most important distinctions that I draw between a “dancefloor” and a “concert.” A dancefloor is co-authored. A concert is typically consumed. That difference changes everything.

Dancers are people who make the party happen by dancing. So much so that some clubs used to recruit and pay especially skilled dancers to come to their clubs because these folks inspired others to dance harder and longer.

In a rave, the DJ isn’t there to perform for an audience, they’re there to infuse the room with sound energy so that dancers can complete the chain by soaking in that energy and converting it into kinectic movement energy.

Look at a picture of a really good dancefloor, and it’s often impossible to tell where the DJ is, because there’s typically very little desire on the part of these dancefloors to face that person.

Concerts, on the other hand, involve a completely different geometry and chain of energy. Attendees may dance (or may simply stand and film), and while it may feel communal to watch a performer together with other people (just as it feels communal to go to a movie theater to watch a film with other people), there is no expectation of co-authorship, and creativity of movement is frowned upon because it can interfere with others’ ability to focus on the performer on the stage.

⛈️ Magical Dancefloors — An interview with Michael Tullberg

After two read-throughs, I sent Tullberg a handful of questions about technique and the evolution of the scene. Here are his responses.

MDF (Magical Dancefloors): Given the breadth of your work and the coverage, how did you decide what moments, DJs, and communities were essential to include?

MT (Michael Tullberg): I didn’t really discriminate between different sub-sections of the rave scene; I was looking to cover as much of it as I could. Part of this was driven by my desire to inject as much variety into my work as was possible, and another part was because I was trying to establish relationships with as many rave promoters as possible. That was key to getting access to all those different events—the building of my professional reputation in the scene. The more events I did and the more promoters I got to know, the higher my profile became, which led to me getting more work and increased access to the events and the artists. Of course, there were some events that I made the extra effort to get into, and many of these were the proto-festivals that grew into full blown extravaganzas, like “Electric Daisy Carnival”, “Together As One”, “Nocturnal Wonderland” and the like.

MDF: Can you walk us through the techniques you relied on to capture the lighting, motion, and energy in this shot? How did you do it?

MT: The shot I made of DJ Frankie Bones behind the turntables is one where I combined a number of my techniques to produce that vibrant, vortex-like image. That was done live at the old L.A. Sports Arena, during the 1999 New Years Eve party “Together As One”, where Frankie stole the show, as far as I’m concerned. As you can see, I was right up there on the stage with him. To produce the lemon coloring of Frankie, I had a yellow gel slapped on my flash head. I decided to do a long exposure, about one to one and a half seconds. I put the camera into a vertical position, opened the shutter, and while rotating the camera in a circular motion, set off the flash in a series of four pops, which produced the stroboscopic effect. The special effects lighting and lasers in the room filled in the rest, combining with the camera rotation to create the swirling energies you see surrounding Frankie.

MDF: If you had to pick one image from the book that you feel best represents the emotional core of the 1990s–2000s rave movement—which would it be, and why?

MT: It’s pretty much impossible to encapsulate all of the various aspects of the rave scene into one image, which is one of the reasons why I put DANCEFLOOR THUNDERSTORM together in the first place. There were just too many ravers, too many artists, too many gigs, and too many amazing moments to reduce it all to one frame. However, if there’s any image that personifies the transcendental moments that people experienced in the rave scene, the moments that elevated their own consciousness beyond the confines of everyday existence, I would pick the abstract shot I entitled “Metamorphosis” on page 128.

More than any other of my photos, that one best illustrates the spiritual expansion that people often underwent on the dance floor, when the energies within them were released in a joyous explosion of emotion. The light shining from within the subject’s heart really illustrates that in a way that a conventional photo can’t. I was actually considering using it for the book’s front cover, but I ended up deciding that it was too much of an abstract image for a casual viewer to immediately understand. That’s the thing about a cover—as an author, you need a shot that everybody can quickly latch onto, even if it’s not your absolute favorite.

MDF: In your view, what elements of the classic rave ethos were lost as dance music moved into the commercial EDM era?

MT: It definitely became more corporate, moving away from the underground ethos that was so vital to the rave scene at its peak. This was unfortunate, but also a bit inevitable, as a scene can’t remain underground forever and expect to survive in the long run. However, with that change also came expansion, leading to increased production values in the parties that could only have been dreamt of in those early days. The visual effects definitely were taken to new heights, as LED walls replaced analog projections, and lighting and laser systems became better and more affordable.

Also, the original rave generation was beginning to age out, while the new EDM generation—the younger siblings and cousins of those founding ravers—were beginning to age in, and bringing new musical tastes with them. This was the audience that would fuel the rise of the festivals, transforming gigs like EDC into the giant mega-festivals that they are today. However, the old DIY ethos of the original rave scene was being left behind, in terms of party production, musical creation, fashion and more. Things became a lot more manufactured, as opposed to being spontaneously created.

MDF: As someone who has shot virtually every music genre, what made the rave community different from other music subcultures you photographed?

MT: The main difference between the rave scene and other scenes that I photographed was that the rave scene was one where both the audience and the art form itself were not only tightly intertwined, but also growing and evolving at the same time. Just about every other scene was based on an existing template, where the audience were expected to come in a certain type of dress code, and listen to a type of music that had already been established. This was true of the Gothic, Industrial and mainstream pop scenes that I had been involved in.

The rave scene, on the other hand, was a grassroots creation that was continuously morphing in new directions that those other scenes couldn’t. Also, most of the established scenes still manifested the various social barriers that subdivide an audience, such as social status, money, sexuality, religion, fashion, geographic location, and others. In many cases, such as in the Beverly Hills club scene that I had frequented, this developed a very clear case of exclusivity, rather than inclusiveness. The idea was to keep certain types of people away, behind the velvet rope. The rave scene threw all of those conventions out the window, which produced a much larger and more diverse audience.

There really was only one criterion: are you a fan of this music? If the answer was yes, bingo, you were in, and you had no restrictions as to how you could express yourself on the dance floor. Sure, there was kandi raver fashion, but it wasn’t a uniform, you didn’t have to wear kandi to be accepted. You could wear whatever you wanted. You didn’t have to worry about being judged, or ridiculed, unless you did something that was really, really out of line.

You could find gang members dancing next to lawyers and accountants and plumbers and off-duty police, and there was no issue whatsoever. There was virtually no violence found in the rave scene, unlike several of the hip-hop venues that existed at the time, and sexual predation was pretty much near zero. It was the mainstream clubs that had the truly nasty date rape drugs like Rohypnol and GHB. I remember unconscious girls being carried out of exclusive high end L.A. clubs like The Gate, and that almost never happened in the rave scene.

MDF: What are your thoughts on the ubiquity of cameras (everyone’s got a phone) at many of today’s commercial raves? Do you feel these cameras have a quieting effect on the wildness of the parties where they’re omnipresent?

MT: I don’t know if the phone cameras quell the wildness of the parties, but they definitely reduce the spontaneous and special underground vibe. It’s like the party becomes just another social event to be seen at for social media, and gathering likes to build one’s online audience, rather than a refuge where you can just cut loose without any regard to how you’re going to boost your presence on TikTok. It’s gone from “dance like there’s no one watching” to “dance like everybody’s watching”, becoming all about “me, me, me”, and that’s rather depressing, in my opinion.

“It’s gone from “dance like there’s no one watching” to “dance like everybody’s watching” TEAAAA

What a great review to a phenomenal book.

The vulnerability is so important. Remember that this was a very different time, where emotions and vulnerabilities were not as openly displayed as they are now. We were also a notoriously un-parented generation, so what you're seeing in these pics are young people being able to connect in ways that they hadn't been able to do or feel much in the past.

Rave lore- with its PLUR ethos, had not existed before in any way or form. And California's youth culture had been incredibly divided on the basis of class and race. So this idea that you could connect like this with everyone was just so enlightening and refreshing to feel. Society had been essentially telling us to divide, and then under our own auspices, we came together. That's truly one of the most beautiful revelations that I've ever felt. We could truly come together in love, and we'd never be the same.

Ravers of 30 years ago absolutely look like those of today! Which is such a joy for me to witness. 30 years later, it's largely the same. The same intensity, life affirming, open, wonderful world gets experienced by young people now.

Still images were our confirmation that there was a scene beyond that of you hometowns; that we were truly part of a massive global youth movement. I couldn't wait until my copy of URB came every month and I could see these incredible pics of the rest of the rave world.