When Despacio ate Portola Festival

After 18 months' of agonizing silence, Despacio made its first-ever appearance in San Francisco

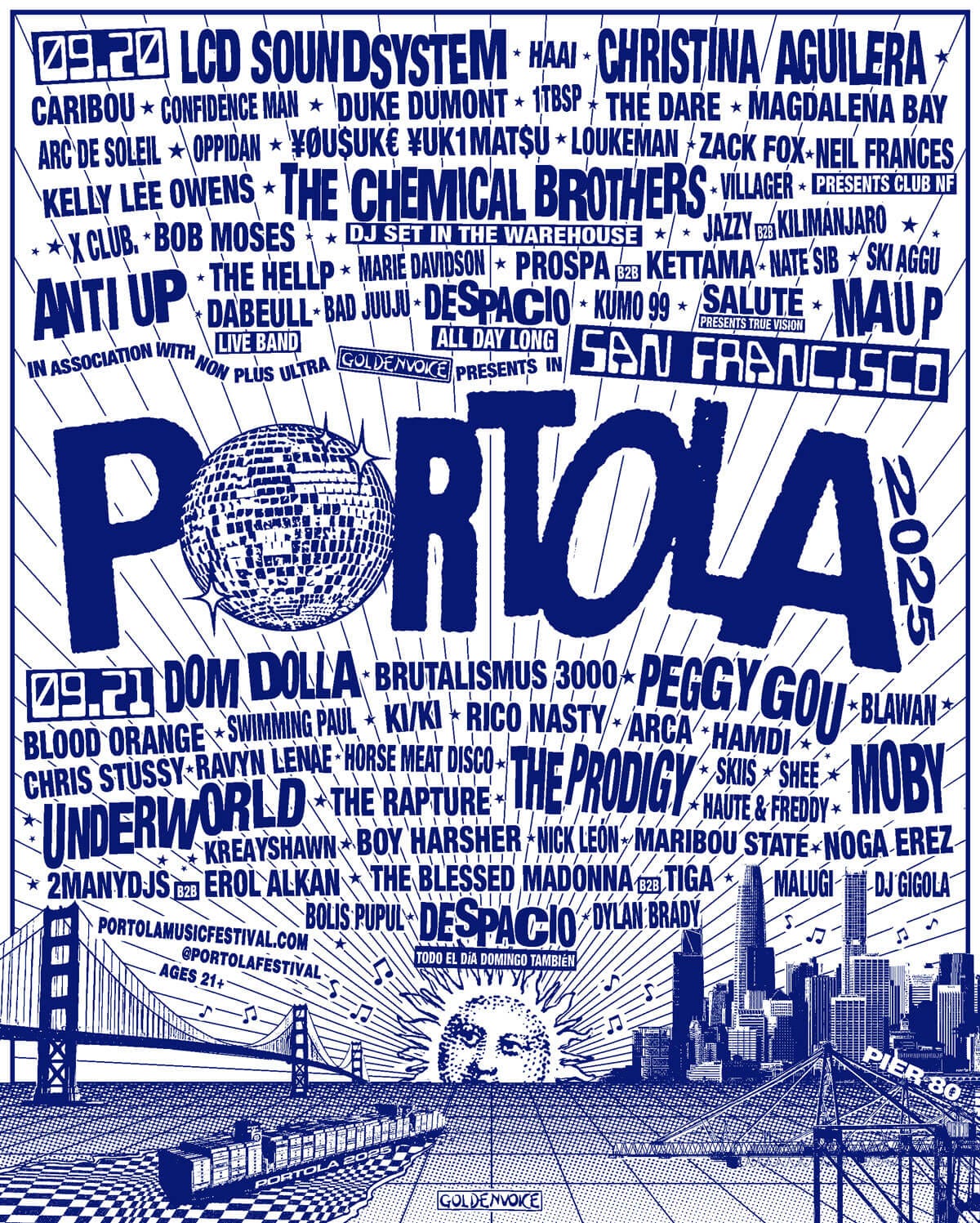

When Goldenvoice shared the lineup for Portola Music Festival, the most frequently asked question about the lineup was “What is Despacio”? The majority of attendees knew nothing about Despacio, and that’s no surprise, given how infrequently this rarest of dance parties happens. After all, it had been 18 months since the prior Despacio event had been held in Ghent, Belgium, and in internet years, that’s a lifetime. It’s hard to sustain -- let alone grow -- a fandom when events are 18 months and ~5,500 miles apart.

And yet, by the end of the festival weekend, the little name on the bottom of the poster had ascended to top billing in many attendees’ minds thanks to its unique combination of body-moving analog sound pumped out of its 100,000-watt soundsystem, meticulous track selection, rebellious design that hides the DJ, one very charismatic disco ball, and social proof that came in the form of lines that at times stretched across the entire festival grounds.

In short, Despacio was impossible to ignore, and for many who entered that tent, impossible to leave. The tiniest tent at Portola upstaged everything else at Portola.

Despacio ate Portola.

A massive system with an achilles heel

The warm reception Despacio received at Portola is in part due to the tireless work of a community who had previously experienced it, become Despacio truthers, and come together on Reddit (r/despacio) and on Discord (discord.gg/despacio) to devise ways to generate demand for an experience that was, since its debut in 2013, entirely too underground for its own good. Its underground status was in large part due to its rarity — it has happened just 21 times since its debut in 2013.

That’s because Despacio has a few huge flaws that make it especially difficult to put on.

The system is massive. The amps and stacks and the boxes in which they’re transported weigh some 66,000 pounds (30,000 kilograms), it’s expensive to store, ship, and set up. Whereas a modern DJ just needs to roll up and stick a USB stick into a “club standard” system, the Despacio system consists of custom everything: specific speakers, amps, cables, lights, turntables, and other equipment that, together, form an integral whole. It’s all or nothing -- there is no scaled-down, plug-and-play version of Despacio.

It’s a side project for the DJs. There are just three people in the world who have ever played on the soundsystem, and the three of them are kind of busy: James Murphy (LCD Soundsystem frontman and DFA Records cofounder) and brothers David and Stephen Dewaele (who perform, produce, and publish under monikers including 2manydjs, Soulwax, Waffles, and Deewee). Without being too explicit, the DJs have been on the record as saying that their fees for Despacio are much lower than they might earn through other appearances -- they’re not raking it in with this project and understandably prioritize more lucrative work. Getting these three artists into the same room, let alone the same timezone, for two or three consecutive days results in a situation where Despacio almost happens six or seven times for every time it actually happens.

It’s somewhat economically unviable. To bring Despacio to a festival, the organizers of the festival need to come up with nearly $350,000 for a 2-3 day run. Despacio’s Portola footprint could fit a maximum of about 2100 people, but was run leaner than that -- about 1,800 were allowed in at any given moment -- making it the most expensive production on a dollar-per-dancer basis at the entire festival. For Portola, a festival with a capacity of about 45,000 people, spending that much money on its smallest stage is a luxury that its talent buyer-in-chief, Danny Bell, could only afford after selling out the festival (and presumably achieving profitability) in 2024.

Imagine trying to make those numbers work out for a standalone event. An event costing $350k would need to gross $116k of tickets, merchandise, and concessions per night over the course of a three-night run. Even if we assign 30% of that to non-ticket revenue (e.g., alcohol and merch), that’s still 2,000 tickets at ~$40 each that need to be sold, per each of three nights… just to break even!

Bottom line, it’s really difficult for an underground event that most people haven’t heard about to muster those kinds of numbers. Despacio’s core team often reminds folks that every Despacio could be the last one, and that’s no exaggeration on their part. It’s hard to sustain a thing like this unless there’s a lot more awareness of it and demand for it.

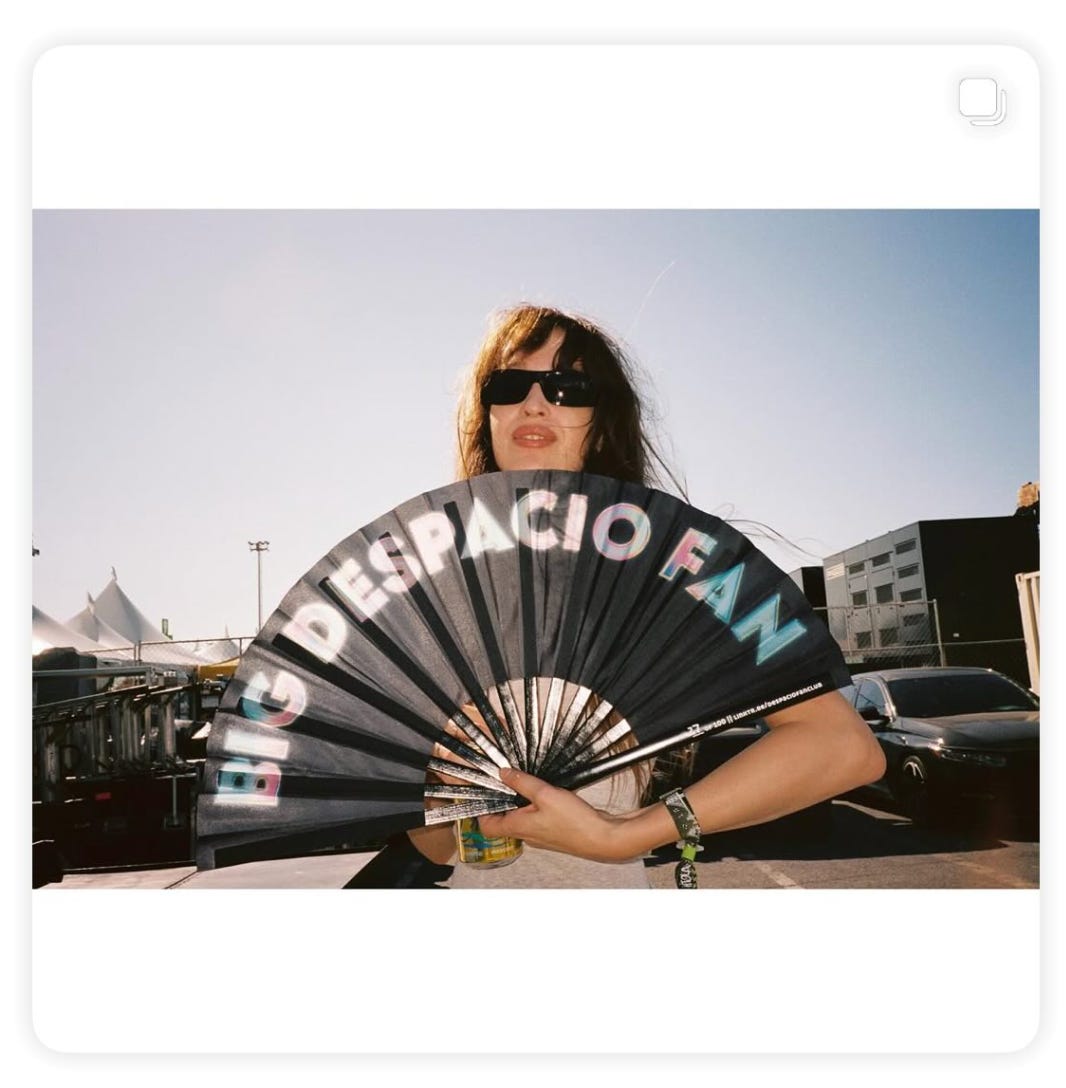

That’s where the community felt it had a role to play. The Despacio community took it on themselves to see what they might be able to do to get the word out. When dancefloors came back to life after the pandemic, a small but tiny contingent of Despacio freedom fighters took on the role of evangelizing Despacio through bootleg merch (shirts, stickers, fans, kandi, etc.), pro-Despacio content (on Reddit, YouTube, Tiktok, Discord, etc.) and even Despacio-inspired dance parties. I was one of these folks -- in many ways patient zero of the post-pandemic Despacio virus after falling hard for it at This Ain’t No Picnic in August 2022. I’ve since spent thousands of dollars and hundreds of hours boosting Despacio for the simple reason that I wanted to see it happen more frequently.

To be clear, all of this community energy was driven by a fire Despacio had lit in the bellies of people who, like me, had at some point unsuspectingly wandered onto its dancefloor unaware that their lives were about to change. Despacio’s undeniable beauty wormed its way people’s heads and hearts and made some of us want to work very hard to help Despacio in any way that we could.

“THEY LIED TO US!”

The line for Despacio started an hour before the doors were scheduled to open. Glenjamn’s fine lens caught the first few folks who were lined up on day one. One of these die-hards (yours truly) would enter the tent and not leave it for seven hours. Not even for water.

Upon entering, we were struck by the darkness and coolness of the space inside the sound-insulated tent, a marked contrast to the unseasonably warm weather outside.

We were immediately struck by how quiet it was — the cross-chatter of sound-bleed from several of Portola’s stages disappeared as we entered, thanks to robust acoustical treatment. Despacio’s production team had thoroughly sound-insulated the Despacio tent to ensure that a repeat of the sound-bleed issues that plagued its 2014 Glastonbury appearance wouldn’t recurr at Portola.

Within 10 minutes, the room reached capacity and the queue outside the tent began to build up again. Over the course of that first day, the queue would wax and wane, snaking across the festival grounds and advertising to the broader festival population that there was something special at the far end of pier 80 that they might want to check out.

Meanwhile, inside the tent, the DJs had decided to pull a fast one on the gathered dancers. Despacio is named for the Balearic sound pioneered by Ibiza DJs — records are frequently played slower than their default setting, sometimes drastically so. Records intended for play at 45RPM might be played at 33RPM, for example. What’s more, Despacio’s DJs eschew climactic moments for the first hour or two. The lights are muted and the room is kept dark. The DJs play slower, moodier tunes under 100 BPM in the first hour or two. They take their time, slowly building the set.

Within a dance music festival setting, taking it slow is an act of rebellion. At Portola, sets were as short as 30 minutes and as long as 1.5h, with the average set duration sitting at around 50-60 minutes. Within the constraints of a 60-minute set, there’s no time for romance or “storytelling.” DJs given just 50 minutes will typically skip the foreplay and jump straight into their money shots, dropping big-energy bangers onto the upturned faces of their social media-addled audiences, then -- after a minimal refractory period -- splashing another big drop onto the audience while the DJ mugs or Christ poses for the phone cameras. There’s a tendency in festival sets for every song played to have drops manufactured in a studio to deliver a big dopamine hit in 15-20 seconds.

Festival attendees in the year 2025 have learned to reach for their phones when they hear a song entering the break, because they know that the “sick drop” to follow might help prove to their followers that they’re “ravers” with good taste. This drop-focused music is designed to be filmed by festival goers, increasing the chance that a producer or DJ’s set might climb the algorithmically gate-kept visibility ladder on TikTok and YouTube.

What’s happened to live dance music events isn’t dissimilar from what happened to the restaurant business once Yelp became a force that could make or break a restaurant. Understanding that how food looked on social media mattered more than how it tasted, chefs started to cook for cameras rather than bellies, and as a result, the stuff that came out of kitchens had a certain built-for-social media wildness to it, such as Bloody Mary cocktails with entire meals poking out of them:

This same trend has been happening to music since the advent of the smart phone put a camera in everyone’s pocket, incentivizing DJs to not just sound good, but look good, and invent antics that make people want to film them. Steve Aoki started throwing cakes in 2011 after smartphones took over, and Fisher’s notorious clown-like antics include descending to the decks on a wire harness, while Mestiza dance with castanets and hand fans, and Peggy Gou lip synchs and dances cutely for an audience who don’t dance, but only film. People who aren’t interested in dancing willingly shell out four figures to watch Anyma’s cheesy CGI music videos at the Sphere. This is the state of much of dance music today -- it’s all about visual spectacle, and dancers are converted into consumers who are taught to prioritize how things will look on their social media accounts over how things feel in their bodies.

We’ve lost dancing.

In commercial dance music, DJs are put on a stage, surrounded by pyrotechnics and high-resolution screens, and all of this spectacle inevitably commands attention. Dancers stop dancing with each other so that they can simply stand shoulder-to-shoulder next to each other while watcing performers on stages.

The dancefloor has been commercially perverted into a concert.

What had been a vibrant dancefloor ecosystem full of rich dancer-to-dancer interaction has become a sad and passive audience of consumers. The consumers pull out their phones to capture and share the spectacle so that more consumers are pulled in to the next concert. Of course the consumers are taught to stand still while filming -- dancing makes for shakey video, and shakey video doesn’t get likes, retweets, shares, or -- ultimately -- the social validation the consumer has been taught to crave.

It’s all rather perverse. Despacio was designed in explicit protest against this inversion of priorities. The Despacio team chose to re-center the dancefloor, and the key to this trick involved hiding the DJs in a booth tucked off to one side. They keep the room so dark that trying to film anything is usually a waste of time. They eschew the pornographic “drops” and short-attention-span theatricals of festival EDM concerts.

Many of the folks who wander into Despacio at a festival such as Coachella, Portola, or III Points are confused by it, at first. Many of the tourists enter and leave after only a few minutes, because they want spectacle and Despacio doesn’t provide it, at least not most of the time.

Take, for example, the college-aged boy who, upon entering, noticed that most of the dancers seemed to be facing the center of the room. He figured he’d found a Boiler Room-style setup with the DJ in the center, so he muscled and elbowed his way past the outer rings of people to get to the center. (Side note: good dancefloor etiquette says that if you can’t dance to where you’re going, you shouldn’t go there.) He and a friend shouldered past me and stepped into the middle, then looked around in confusion.

“They lied to us!” he shouted to his buddy. “There’s nothing here! Just people dancing!”

“That’s the point!” I said to them as they shoved their way back towards the exit. Never saw them again.

LIKE A DOG WITH A CHEW TOY

But there was some mischief afoot in the DJ booth. Just a few songs into the day, they eased into a 92bpm track that Despacio veterans recognized immediately due to its distinctive, synthy bassline. We had just entered Edwin Starr’s Whirlpool of Love (Eric Duncan Edit) and knew that this was a track that the DJs typically played much later in the day, when they were ready to bring the room to a frenzy. I checked my watch -- we weren’t even 30 minutes into the seven-hour set, and they’d just loaded up a track that was going to kick the party into a much higher gear.

If it sounds like I’m protesting, I’m not. I like that the DJs keep things unpredictable, breaking from their own conventions frequently. But they took us all by surprise when they dropped the needle onto a record that would have the disco ball at the center of the room ignite in fire. I checked my watch to be sure and caught another Despacio veteran doing the same -- we looked at each other, smiled and shrugged, our looks communicating, “so I guess it’s gonna be like this, then. Buckle up!”

By the time the song had completed its spins, the room had been jolted out of slumber. True to the song’s lyrics, we were now “just a lot of funky people with a whole lotta soul, dancin’ all over the place.” Folks had broken a sweat, the hand fans were fanning, and there was a post-climax glow on dancers’ flushed cheeks. Despacio Portola was off to a head start.

It felt like the DJs were like a dog with a chew toy. They’d grabbed hold of the room with their teeth and were furiously shaking their heads, knocking off the dust and ache of an 18-month hiatus since the prior Despacio in Ghent, Belgium. The way I interpreted it, they weren’t fucking around.

Perhaps the system wasn’t quite ready for them to go quite so hard. Shortly after Whirlpool of Love, I detected a loose and sloppy kick drum that sounded like a blown sub. Perhaps a plastic bottle had been sucked into the subwoofer. It was triaged quickly, and the sound returned to its pristine state, but it was a little reminder that perhaps gremlins take a while to be exorcised from systems that sit in storage for criminally long periods of time.

By the end of day one, quite a few of us felt like we’d blown an emotional speaker. We’d been ridden hard by the DJs, and the tears had flown freely, thanks to a closing hour that wrung every last drop of dance juice out of our limbs:

At the end of the day, as security worked on shooing everyone out of the room, the Despacio Fan Club gathered for a photo, this one taken by the legendary lens of Babycakes Romero, Despacio’s original official photographer.

Stories

There isn’t a Despacio — or any dancefloor for that matter — without stories. Here are some of the stories I became aware of over the weekend. If you’ve got one to share, feel free to reach out to me -- would love to add yours to the mix here.

The proposal. At about 5pm on that first day, a group of friends had been told they were to meet under the disco ball, but weren’t told exactly why. Once the group had assembled, a man dropped to one knee and asked his girlfriend to marry him. The song playing at the time was Ba Ba Go, Go by Topo, a funky, 1983 Italo-disco track with strange cat meows, a wonderful bassline, and the fitting lyrics, “I love you.” A cheer went up in the crowd when the proposal was accepted, and the DJs were quite confused, because they’d played the song several times at prior Despacios and it had never inspired such cheering.

There were two other moments where random cheering broke out.

They found Gilligan. One of these moments happened when a group located a long-lost member of their squad inside Despacio. I’d been dancing next to him for a bit and he was going for it. Lost in the sauce, totally locked in, just grooving his heart out. Suddenly, I hear someone yell “I found him!” and a group descended on him and started cheering and patting him on the back. Turns out, he’d been separated from the group for hours, and they had been looking everywhere for him. I don’t know the exact story, but I’d like to think that Despacio is like the realm where lost socks go. It’s a twilight zone where lost people can go to find themselves and disappear from the world for a while.

Marie Davidson. Marie Davidson, an artist with the Deewee label, spent hours dancing with us at Portola. She’s not the first artist to spend some serious time on the Despacio dancefloor, and she won’t be the last, but we were especially delighted when the DJs surprised all of us by playing the pre-release Deewee Dub of her Push Me Fuckhead record (the release of this version of the song is scheduled for October 31). The energy of that moment, her smiles, the excitement of everyone around her as they recognized what was happening -- it was a piece of dancefloor magic. Here’s a short clip of that moment.

A high ball. At another time, I heard some cheering, again coming from the center of the room. In this case, a man had brought a construction-style measuring tape and was standing under the disco ball, trying to measure the height to the ball. The measuring tape kept flopping over at the last moment, causing folks to cry out in anguish. Finally, the tape reached the ball and the crowd cheered in triumph. I of course needed to know the number, so I asked him for it. He had measured the ball at 8 feet and 3 inches off the floor. Turns out he was high (literally and figuratively speaking) and the bottom of his ruler wasn’t even on the floor -- so the number wasn’t exactly useful.

I don’t think folks should try to touch the ball, and so I’m not telling this story to encourage anyone else to find the actual height of the ball at a future Despacio. But I do enjoy a bit of play so long as it doesn’t undermine the dance party. This moment brought people together and seemed wholesome enough.

The music: The selections for Portola stayed true to the Despacio version of the Balearic sound that 3manydjs have pioneered. Jump into this spreadsheet to explore over 180 records that the community identified as being played at Portola. Maybe you’ll even be able to help us identify some of the music we haven’t been able to identify yet. One notable difference between the two days: on day one, James Murphy went missing for a couple hours to serve as frontman for LCD Soundsystem, who were also performing at the festival. On the second day, 2manydjs disappeared for a couple of hours to play a set on another stage at the festival. We had a lot of fun comparing the difference in track selection and energy when it was James only in the booth vs. 2manydjs only in the booth. Normally, Despacio is a blend of the two styles, but during these rare moments, we hear the blend pulled apart and we develop a clearer sense of what each side of the DJ team brings to the table.

At the heart of Despacio are great records played on a wonderful hifi system into a dark room to people who are down to dance to whatever the DJs want to play. The selections made by these three DJs redefine what it means to be a selector — there is very little in the world of DJing that goes as deep.

The original Capy. One of the songs that has endeared itself to many is Capy, the Manncool & Trol2000 edit of Capone’s Music Love Song. At Portola, for the first time in our recorded history, the DJs played Capone Love Song, pitched way down. The original is a beautiful song, and it shines in Despacio, but to be honest, doesn’t hold a candle to the Manncool & Trol2000 edit, which deeply improves the song by turning the “I love you” lyric into a chorus that repeats some five or six times. Without the repetition, the song fails to deliver the same emotional punch.

We spent some time wondering why the DJs would choose to play the less effective original version of the song, and we learned that the original had been re-issued by Sound Metaphors in December 2023, and that Sound Metaphors had, in 2024, issued some strongly worded cease & desist letters to folks who had published unlicensed edits of the music online. We don’t know for sure, but we’re guessing that the Sound Metaphors lawyers asked the DJs (nicely or not nicely) to stop playing the unlicensed Manncool & Trol2000 edit, and so the DJs played the original version.

So the first thing I did when I got home from Portola was dig my “Capy” record out of its crate and put it on my turntable. It was as good as remembered.

Another one bit the dust. In an example of the most spectacular sound glitch I’ve ever heard in my nearly 100 hours inside Despacio, a bit of dust got between the needle and Queen’s Another One Bites the Dust as the record spun. For a few agonizing seconds, the record skipped and sounded absolutely terrible. Dancers halted mid-move or contorted into an imitation of the tortured sound. A collective groan rose in the room.

And then, somehow, the record was back on track, and the party, reminded of the mortality of vinyl records, seemed just a little bit more thankful for the flawless sound that followed. I overheard someone near me remark, “whoa, this is vinyl?” Until that moment, they hadn’t even known.

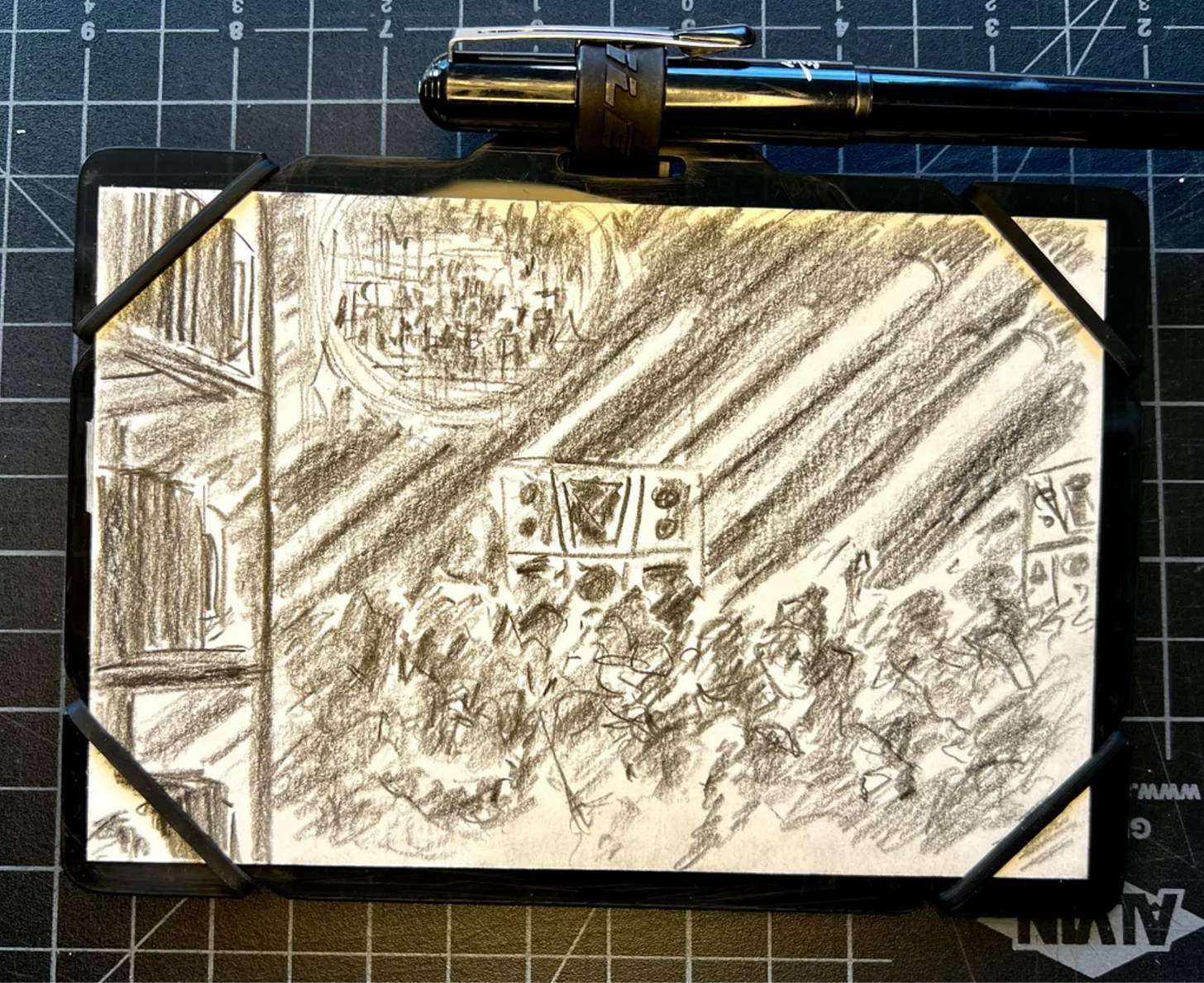

Drawing in Despacio. Yes, the dancefloor is for dancing, but I love when an artist takes the time to stand on the sidelines to capture the essence of the floor, as redditor Lowfi_steve did when he sketched the dancefloor. “I’m an artist and designer and I invented this drawing board to draw on my bike rides (it attaches to the stem). Laaaaate Saturday night, I had the silly idea of bringing it on the dancefloor on Sunday. I easily spent half of Sunday in that tent dancing, drawing, and having the time of my life. It was definitely one of the most challenging and fulfilling environments to make work in, and I already know how to make it even better for next year.”

The heat. San Francisco was unseasonably warm on the weekend that Despacio made its debut there, and the tent Goldenvoice erected to house the happiest dancefloor on earth was not up to the task of keeping it cool. We’re surprised, because this was apparently the same configuration used at Coachella, where daytime temps are often 100 degrees or more. The HVAC system just didn’t seem to want to keep up with all the bodies sweating it out inside the tent, resulting in complaints that the room felt too hot, too swampy, and too crowded. Personally, I thrive in hot rooms because I’ve got a massive fan to keep myself and those around me cool, but I understand the complaints because it did feel a few degrees warmer than we’d want it to be.

Those of us with fans were super happy we had them, and — true to the commandments of the fan club — we were happy to share our breeze with others.

The cameras. Here’s where we get to the most negative thing I have to say about Despacio at Portola. I have never seen more cell phone cameras held aloft on a Despacio dancefloor, ever. (Miami to Portola: “hold my beer” -- we’ll get to Miami and how much worse it was in this regard in the next review.) This Despacio was located just a few miles away from the global headquarters of the companies that make Android and Apple smartphones, so perhaps it’s not surprising that these devices seemed to be in near constant use on the dancefloor.

Let me share a video with you:

This video was taken during a song where, for the most part, everyone was dancing without a phone in the air until the disco ball was lit up from all sides by dozens of Robe Megapointe light fixtures. Suddenly, the dark room became photogenic, and a number of folks stopped dancing so that they could film the disco ball in all of her glory.

But the problem is that this filming subtracted from the energy on the dancefloor. These moments where the ball lights up are chosen specifically because they’re peak energy moments and it’s especially problematic if someone stands still during what should be a moment of collective effervescence and shared climax. It’s like someone taking a knee during the national anthem, or someone remaining seated when a whole room rises at a ceremony. We can clearly see and feel the dead energy of the people who are filming in this video (including the person who took the video). We can observe how their stillness removes them from the scene and causes others around them to have to move around them as if they’re obstructions, rather than people.

I chose this clip because it shows the impact of just a few cameras. There were many other moments across the weekend when there were hundreds of cameras held up. During these moments I could look across the floor and see a stillness that had never existed when phone use at Despacio was rarer. Despacio’s dancefloor is being silenced by the creeping erosion of dancefloor etiquette.

This is a big problem for Despacio. There are a few ways for the team to handle this, but I’m going to go on the record as saying that I believe the solution needed is one that works at my favorite clubs including Pikes Ibiza, Nowadays NYC, Berghain Berlin, and Stereo Montreal. It’s simple: ban phone photography from the dancefloor.

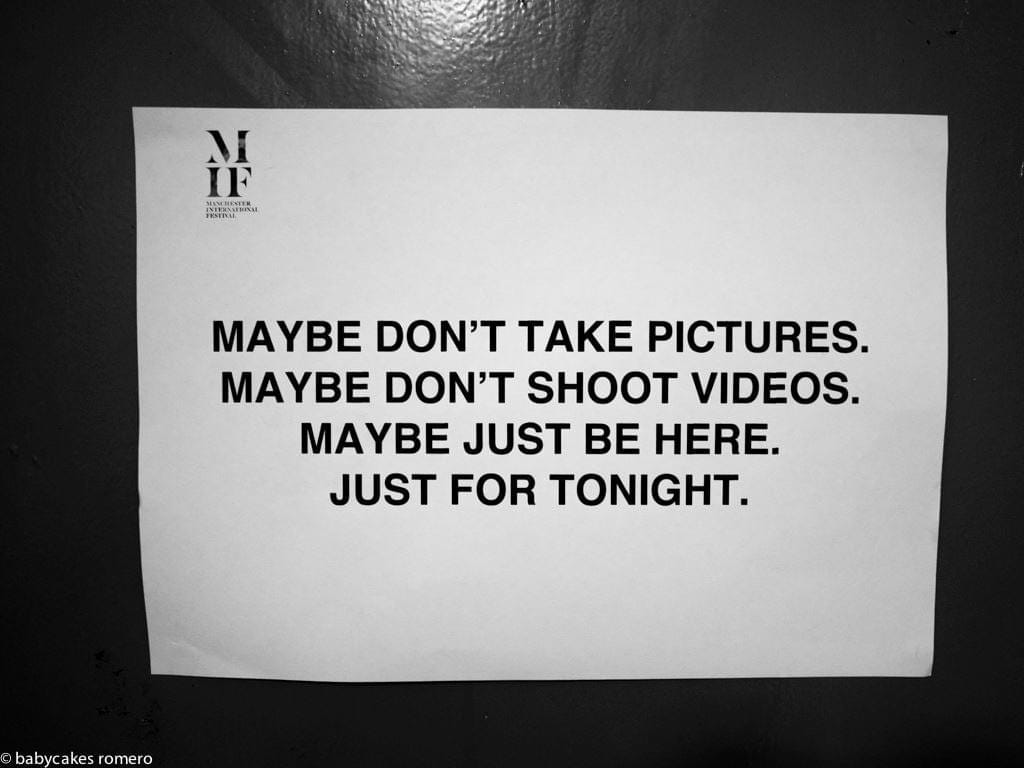

Despacio’s next event is rumored to be a standalone event in NYC. I believe that this event should be announced as a “no photos” event, that cameras should be stickered on entry, and that security should talk to and/or remove folks who break this simple rule. Doing so would be consistent with the founding ethos of Despacio, where the first shows had a sign like the one pictured here that encouraged people to stay off their phones and simply enjoy the moment:

Such gentle encouragement no longer works, some 18 years after the introduction of the smartphone. There’s a whole generation of dancers who grew up with phones and who never experienced a dancefloor without phones. For these folks, the EDM concerts they attend are full of phones held aloft, oftentimes for the entire event.

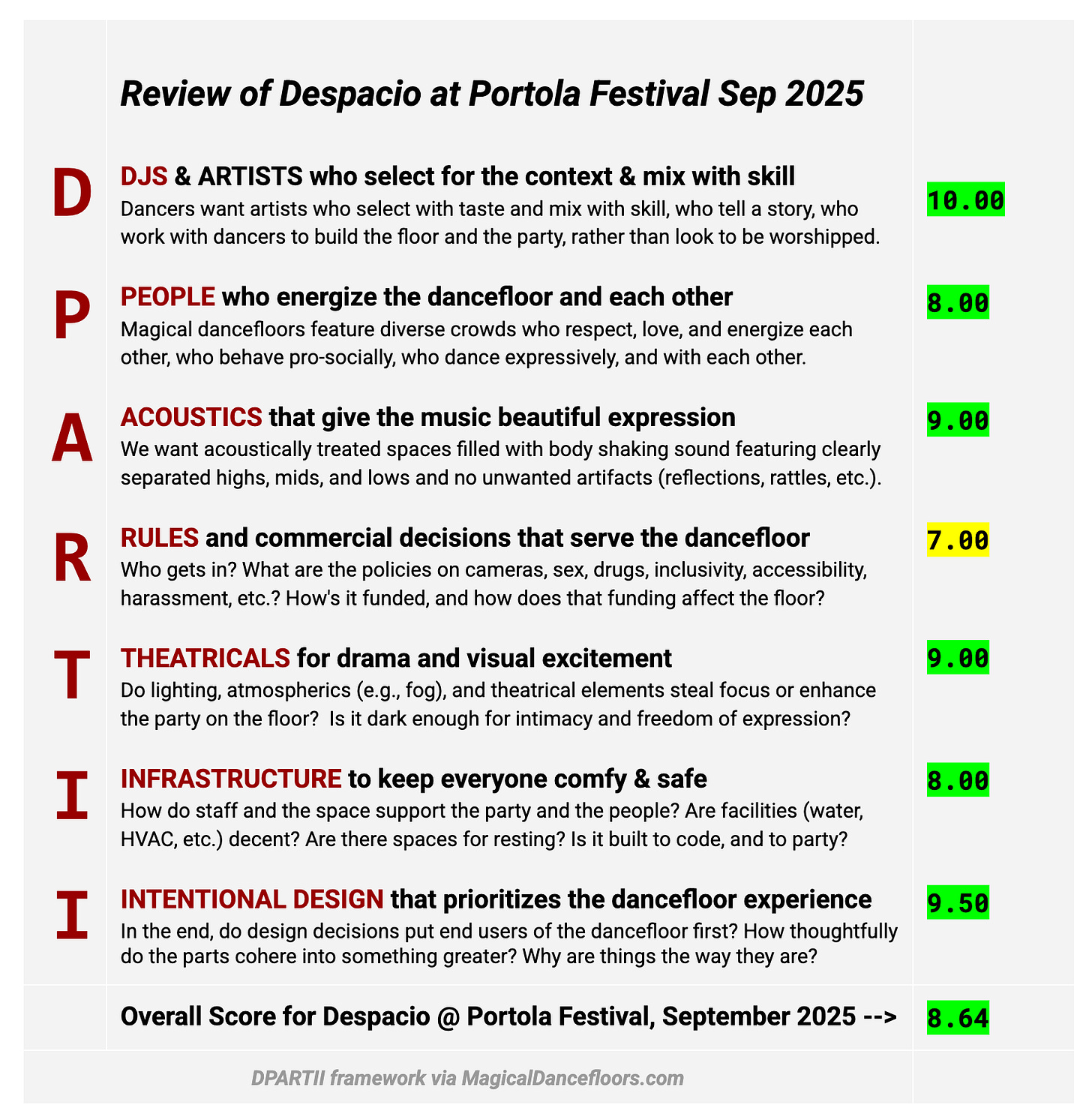

But unless Despacio takes a stand, it will continue to see its highest energy moments undermined by tourists stepping out of the dance to take souvenirs and keepsakes. This is not what I want to see happen to my favorite dance party on earth, and yet it’s already happening. In the scorecard below, Despacio is getting a “RULES” score of 7 for the lack of a phone policy, and the PEOPLE of Portola are getting a (rather generous, considering the level of phone use) 8 for forgetting that the dancefloor is for dancing. I can see both of these scores trending lower over time if the organizers don’t put into place a more muscular set of anti-phone policies.

Despacio cannot maintain its prominence as one of the best dance parties on earth if it doesn’t do something about the phone camera situation. We do not need our Bloody Mary piled high with fried foods to rank better in the social media game of who went to the better party over the weekend. We do not need our dancefloor enshittified by tourists taking photos. Dancefloors are participatory. Dancefloors are for dancing, not for photography.

This request may be a tall ask if Despacio is going to be part of a larger festival where it’s now common for people to stand and film (and not dance). But for a standalone event such as the one being mooted for New York City next year, this request seems reasonable.

Despite the minor annoyances (e.g., the heat) and the major annoyances (the phones), Despacio made the festival for many attendees, me included. I was the first one onto and the last one off the dancefloor on each of the two days, and did not leave once for water or rest because I would not have been able to bear missing a single song played during the 14 hours that the DJs spun records over the two-day event.

Despacio changes lives

Hundreds of folks took to the internet after the event to talk about how the event had changed their lives. The Despacio Discord (discord.gg/despacio) gained a couple hundred new folks, all of them eager to discuss and process the experience.

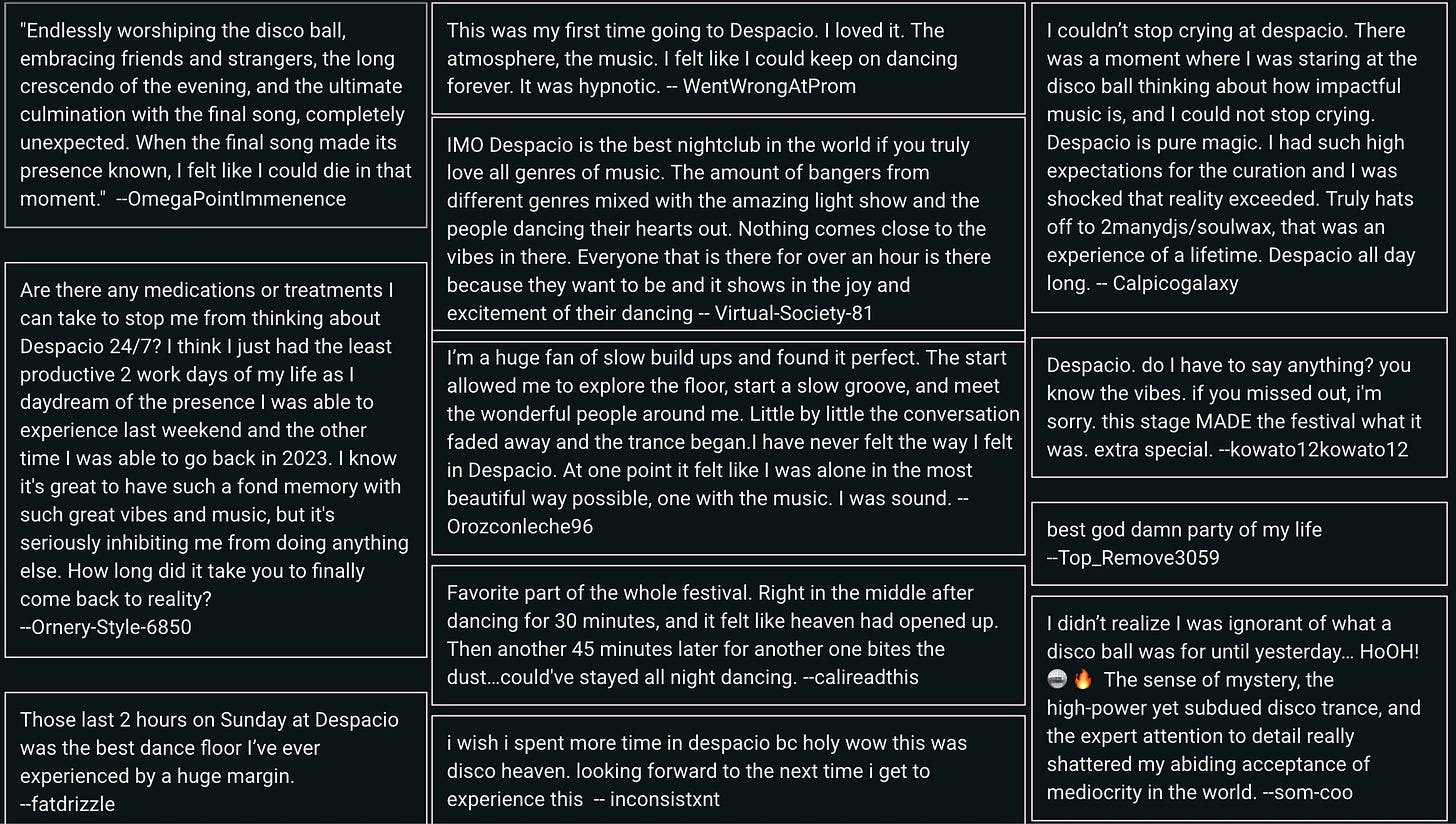

Select quotes:

I like ending on this positive note before giving Despacio the lowest score I’ve ever given it. I think it’s time for Despacio to address the elephant in the room.

Great review..so many great moments..I missed the dude with the tape measure...haha, he coulda just asked ; )

As a photographer I might be doing myself out of a job here but I kinda agree with you on the photo/phone front..the irony is that they tucked away the booth cos they didnt want everyone facing the same direction so they would dance with each other and now everyone faces the mirrorball waiting for it to do something.

My only thing I'm not sure about is even if they didnt have their phones out would they still be facing the ball? I watched the crowd in portola and at Miami and it looked like a congregation in worship..in the very beginning of humanity they worshipped the sun way before organised religion came along..and everyone mesmerised by the giant glowing orb hanging from the middle of the floor looked a lot like that so maybe its just something we need to do?

But IMO i so much prefer it when everyone is dancing together and not facing one direction. Thats the best bit about Despacio. I spent most of the time under the glitterball because it was the only place where people weren't staring at it!

Great write up my friend!

I had the best time of my life at Despacio Miami.

Would love to see some intention put towards the phone issue, and continued thought and discussion around how we protect and promote an actually engaged, participatory dance floor. I think community development is a good first step, as more of us die-hards can come together and be vibe guardians of sorts.

The more Despacio heads are in the room, the more dancing, engagement, and excitement there is going to be naturally and just maybe that will have some influence on visitors and newbies.

But a little priming of people before they enter+stickers would be the most immediately effective I think.

Phones discourage both the user and those in their vicinity from dancing and being present which feels antithetical to what Despacio is.